A Very Informal Derivation of d Orbitals

Partially adapted from various Inorganic Chemistry lectures and Professor Hyungjun Kim’s CH502 Quantum Chemistry I lecture.

Introduction

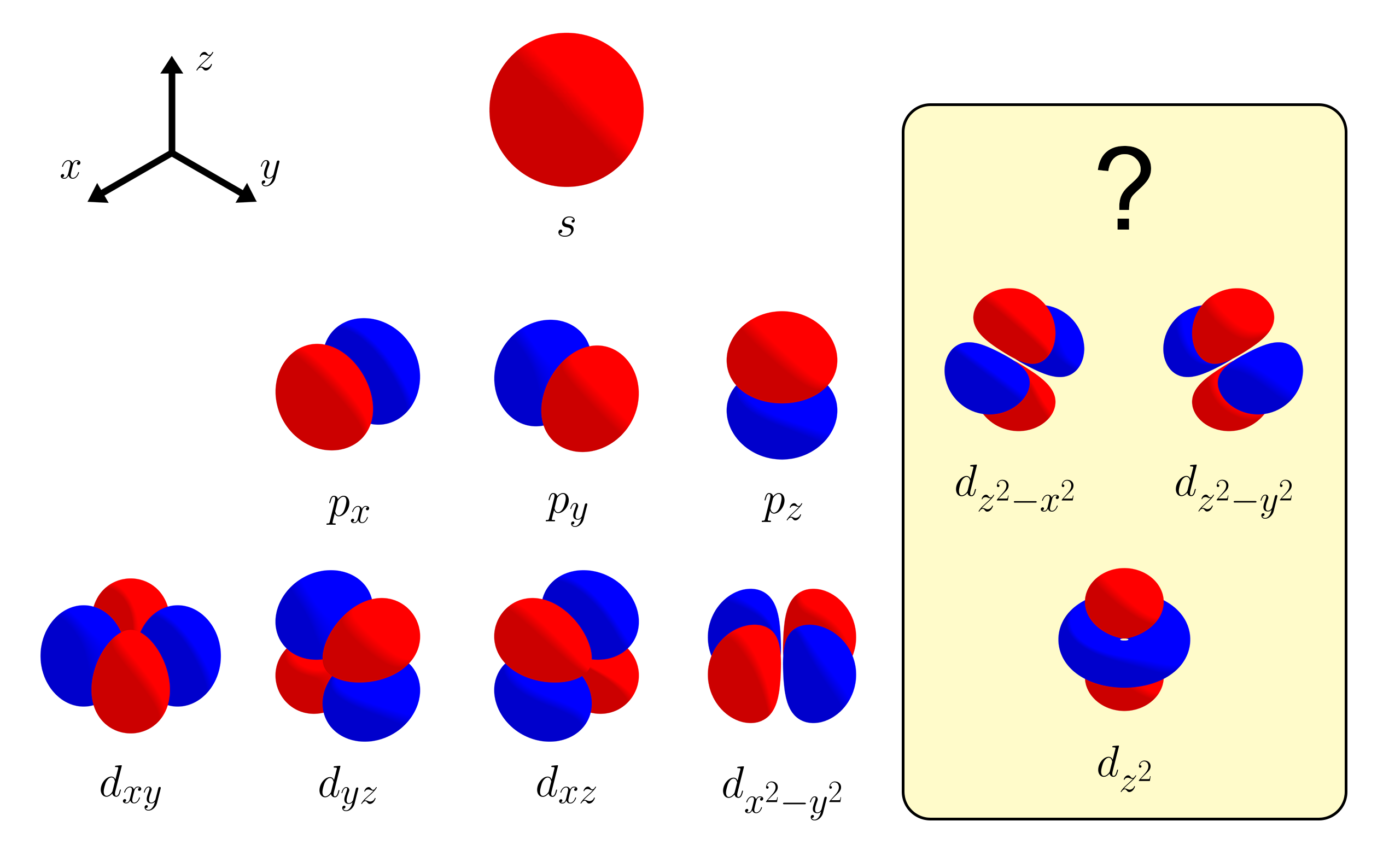

Among atomic orbitals, the most interesting orbitals are arguably the $d$ orbitals. Not only are they important in inorganic chemistry and organometallic chemistry, they also look more interesting than the simpler $s$ or $p$ orbitals without being too complicated like the $f$ orbitals.

Among a set of five $d$ orbitals, the orbital with the most interesting shape is the $d_{z^2}$ orbital. How come other $d$ orbitals have four symmetrical lobes, where as the $d_{z^2}$ orbital has two opposing lobes with a ring in the middle? In this article, we figure out why the $d_{z^2}$ orbital has this unusual shape by deriving it in a very simple way.

A Simple Trend?

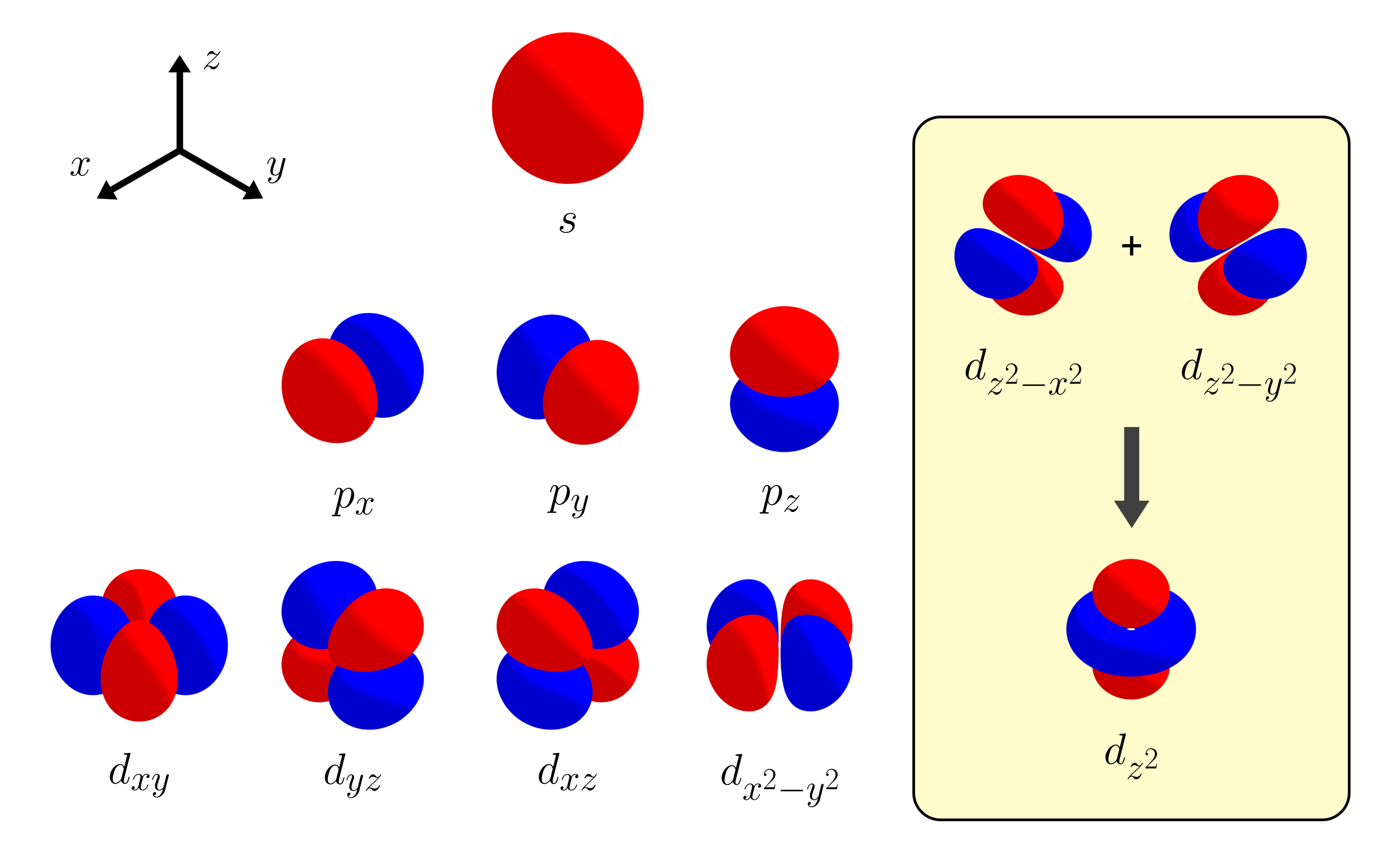

Let’s look at the trend of the orbital shapes as we go from $1s$ → $2p$ → $3d$. We will only consider the angular properties of orbitals while ignoring any radial aspects. The $s$ orbital is just a sphere - same from all angles with no angular nodes. The three $p$ orbitals each consist of two opposing lobes, pointing at $x$, $y$, and $z$ directions. They each have one angular node that separates the two lobes (the nodal planes being $x = 0$, $y = 0$, $z = 0$). From this observation, you would expect the $d$ orbitals to each have four symmetric lobes with two angular nodal planes inbetween them.

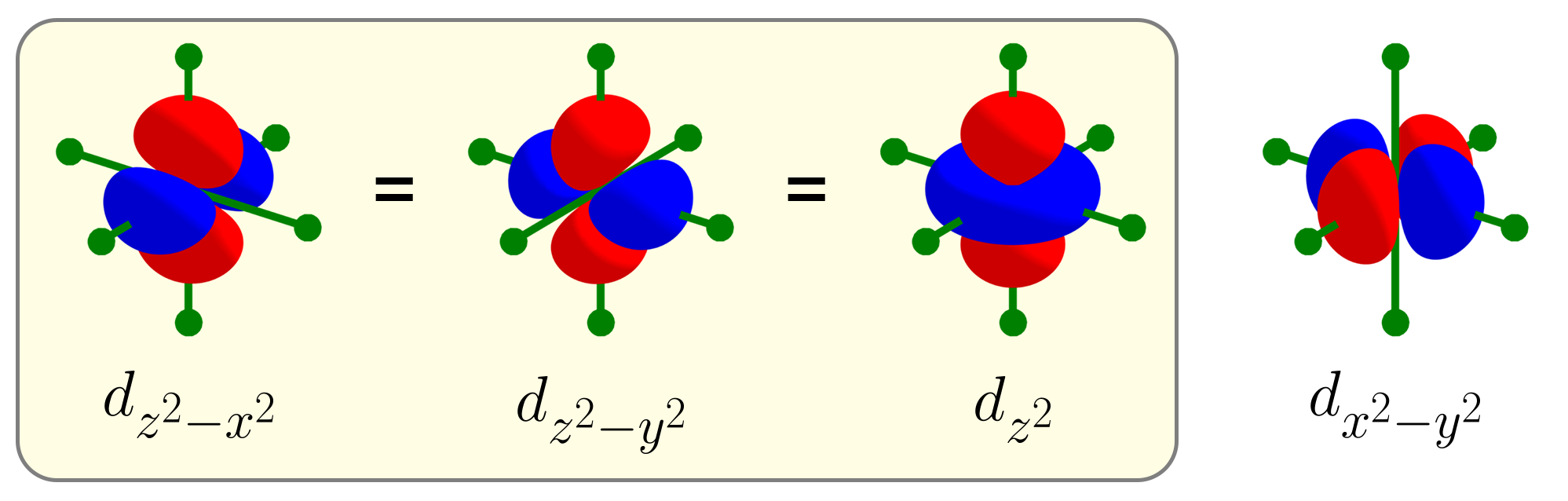

Indeed, some of the $d$ orbitals follow this line of thought. We have the $d_{xy}$, $d_{yz}$, and $d_{xz}$ orbitals, sharing the same nodal planes as the $p$ orbitals. You also have the $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ orbital by slightly rotating the $d_{xy}$ orbital by 45 degrees. However, unlike in general chemistry, you could also have the $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ orbital and the $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ orbital. If so, why do we have the $d_{z^2}$ orbital instead of the two other $d$ orbitals? Why are there five $d$ orbitals instead of six?

To answer these questions, we must know a bit about linear algebra and the concept of linear independence. First, functions can either be multiplied by a constant or be added to each other to form a new function. In other words, you can create a new function by linearly combining various functions. This is because functions are “linear objects”. Coordinate vectors in 3D are also “linear objects”. This is because they can be multiplied by a constant (which adjusts their magnitude or flips their direction) and be added to each other (like with the parallelogram method).

We have a particular name for “linear objects” that can form linear combinations: vectors. You may think that the term “vector” is synonymous with “coordinate vector”, but coordinate vectors are just one type of vectors. Functions are vectors, and as orbitals are 3D functions, they are also vectors as well.

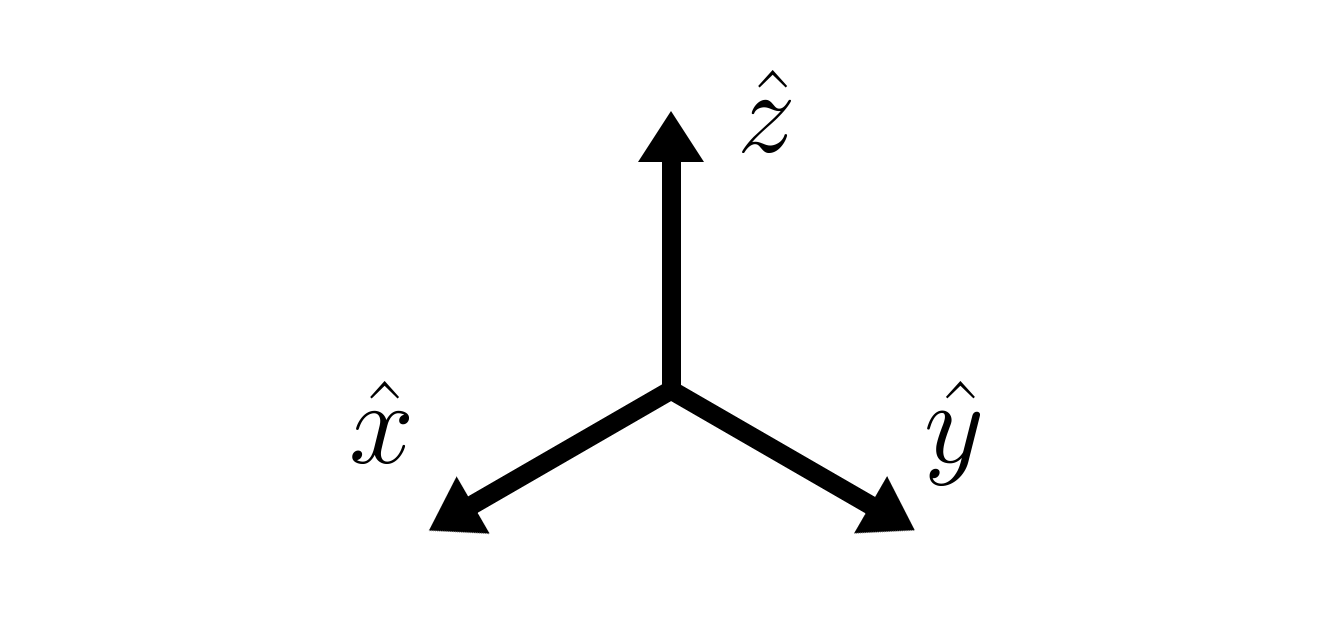

Moving on to linear independence, suppose we have a set of vectors. When any vector in that set of vectors cannot be produced by a linear combination of the rest of the vectors, then that set is linearly independent. The concept of being linearly independent is best shown with 3D coordinate vectors.

The set of three unit vectors $\hat{x}$, $\hat{y}$, and $\hat{j}$, each in the $x$, $y$, or $z$ direction respectively, is linearly independent. This is because you cannot obtain the unit vector $\hat{x}$ with any linear combination of unit vectors $\hat{y}$ and $\hat{z}$, as $\hat{y}$ and $\hat{z}$ are perpendicular to $\hat{x}$. Any linear combination of $\hat{y}$ and $\hat{z}$ would be perpendicular to $\hat{x}$, so the linear combination cannot form the $\hat{x}$ unit vector. The same goes for $\hat{y}$ and for $\hat{z}$, making the set $\left\{\hat{x},\, \hat{y},\, \hat{z}\right\}$ linearly independent1.

This is the same for atomic orbitals. Take a set of $p$ orbitals for example. Roughly speaking, the $p_x$ orbital corresponds to the unit vector $\hat{x}$, the $p_y$ orbital to $\hat{y}$, and the $p_z$ orbital to $\hat{z}$. Therefore, roughly speaking, a set of $p$ orbitals should be linearly independent. To really check if a set of $p$ orbital is linearly independent, we need to have a way to determine if two orbitals are perpendicular (more precisely, orthogonal) or not.

The formal definition of orthogonality between two orbitals $f(x, y, z)$ and $g(x, y, z)$ is something like the following2:

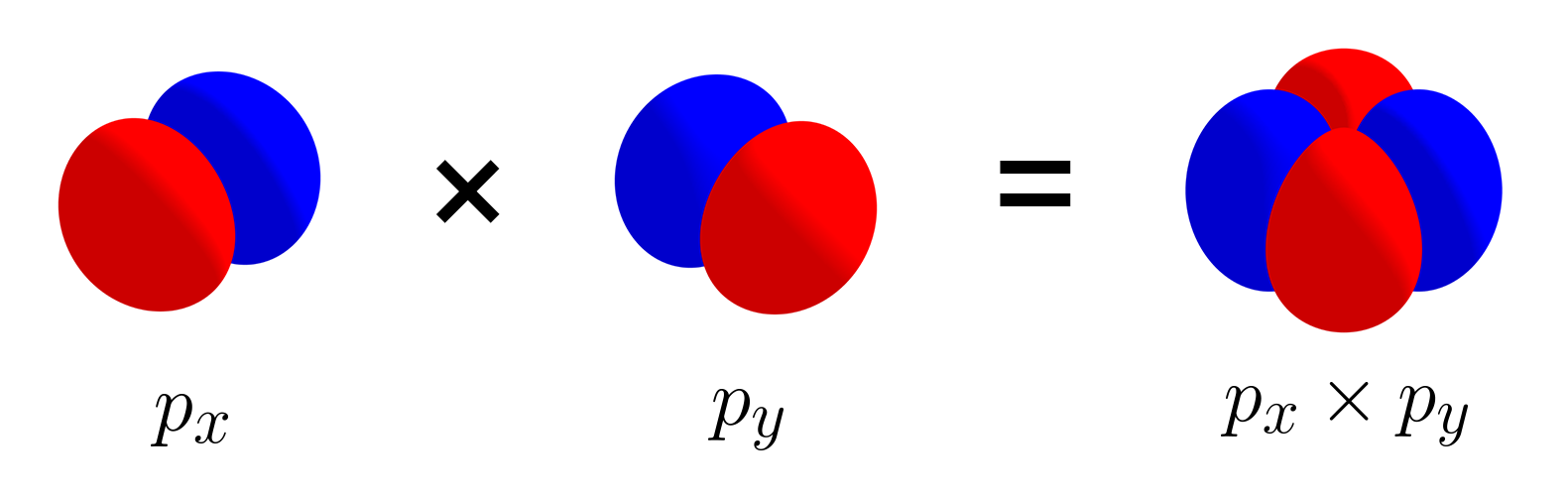

\[\int_{\text{all space}} f(x, \, y, \, z)\times g(x, \, y,\, z) \,dV = 0\]For highly symmetric functions like atomic orbitals, it is possible to determine orthogonality based on the symmetry of $f(x, y, z)$ and $g(x, y, z)$, instead of fully carrying out the integration above. If the product of $f(x, y, z)$ and $g(x, y, z)$ result in equal amounts of positive parts (red) and negative parts (blue), then they are orthogonal, because the integration over all space cancels out.

For $p_x$ and $p_y$ orbitals, the product has two positive parts and two negative parts, all equally sized. Therefore, the two orbitals are orthogonal. Likewise, $p_y$ and $p_z$ are orthogonal, and $p_x$ and $p_z$ are orthogonal as well. Therefore, just like the set of three unit vectors, the set of three $p$ orbitals is linearly independent.

d orbitals

With the mathematical details out of the way, let us discuss about $d$ orbitals. Like $p$ orbitals, a set of $d$ orbitals should be linearly independent. Previously, we supposed that a set of $d$ orbitals could contain six $d$ orbitals rather than five: $d_{xy}$, $d_{yz}$, $d_{xz}$, $d_{x^2 - y^2}$, $d_{z^2 - x^2}$, $d_{z^2 - y^2}$. The question is, are these $d$ orbitals linearly independent?

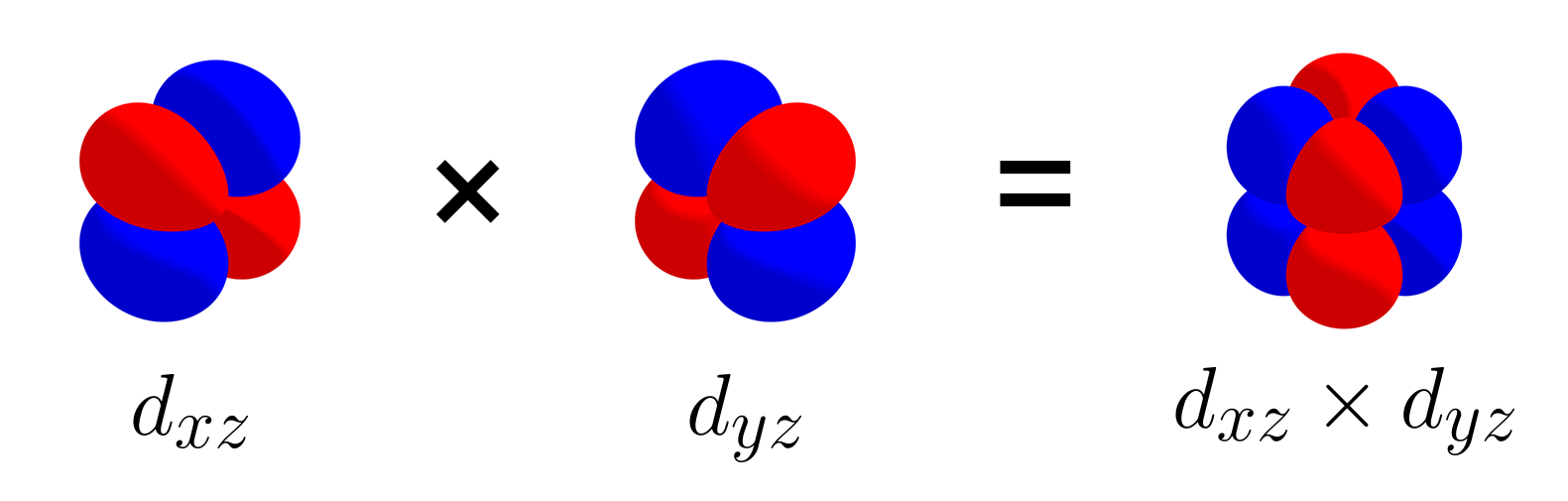

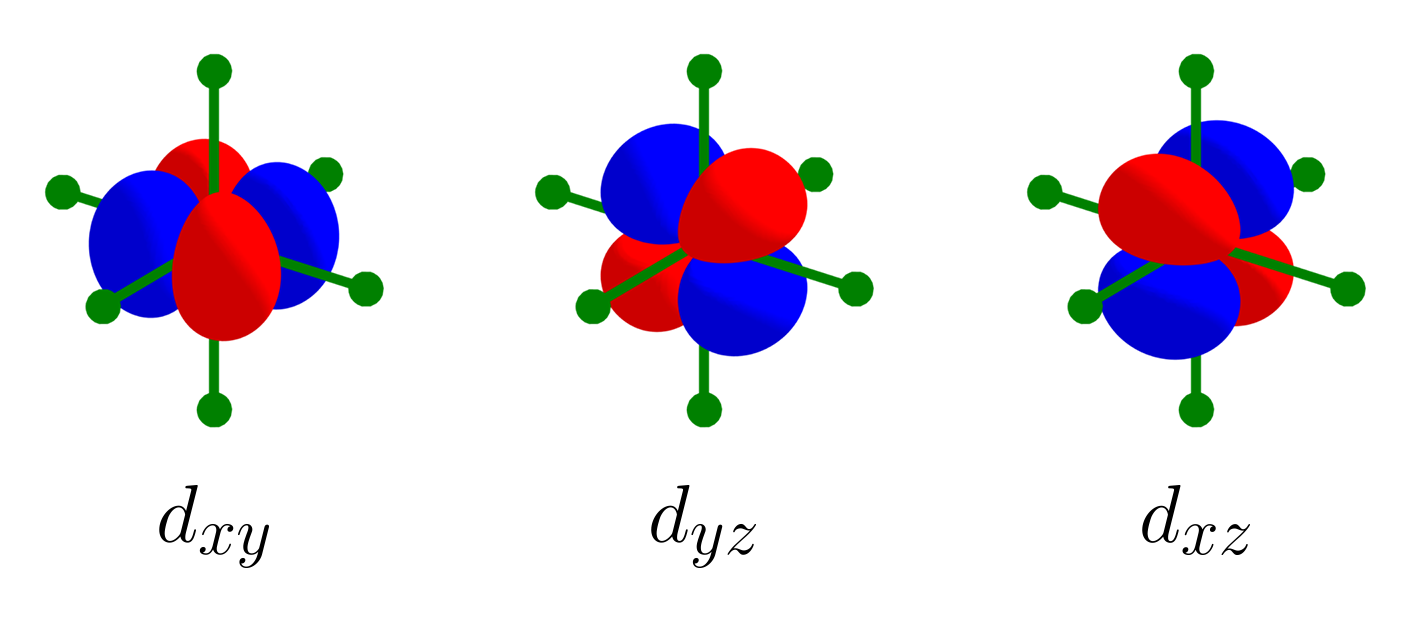

To begin with, let us start with a set of three $d$ orbitals: $\left\{d_{xy},\, d_{yz},\, d_{xz}\right\}$. The picture below shows that the $d_{xz}$ orbital and $d_{yz}$ orbital are orthogonal.

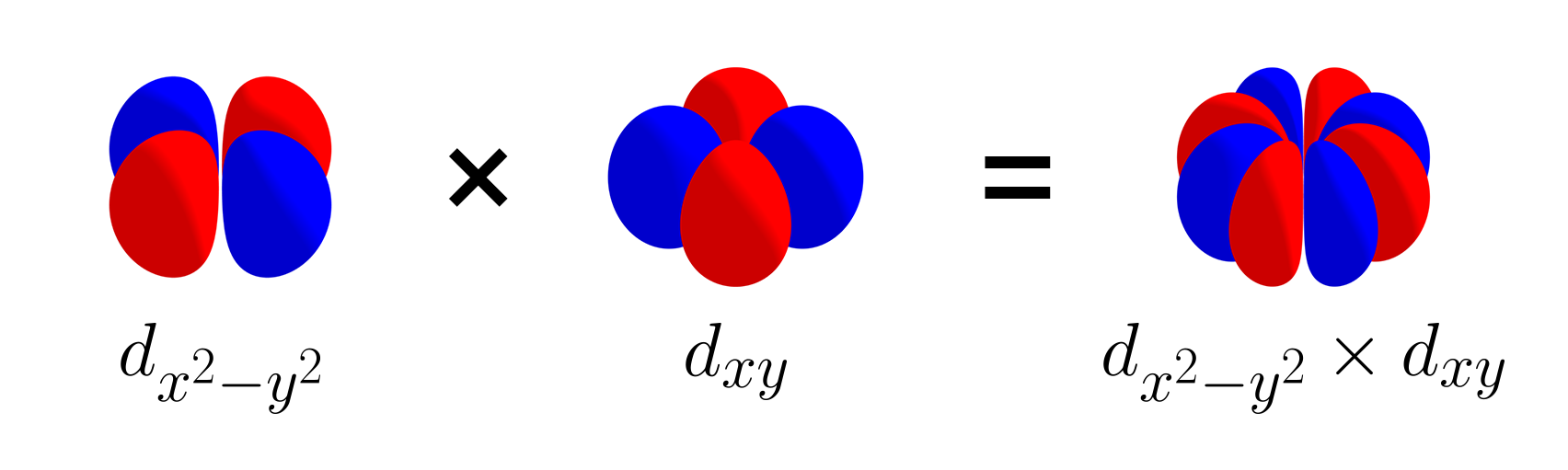

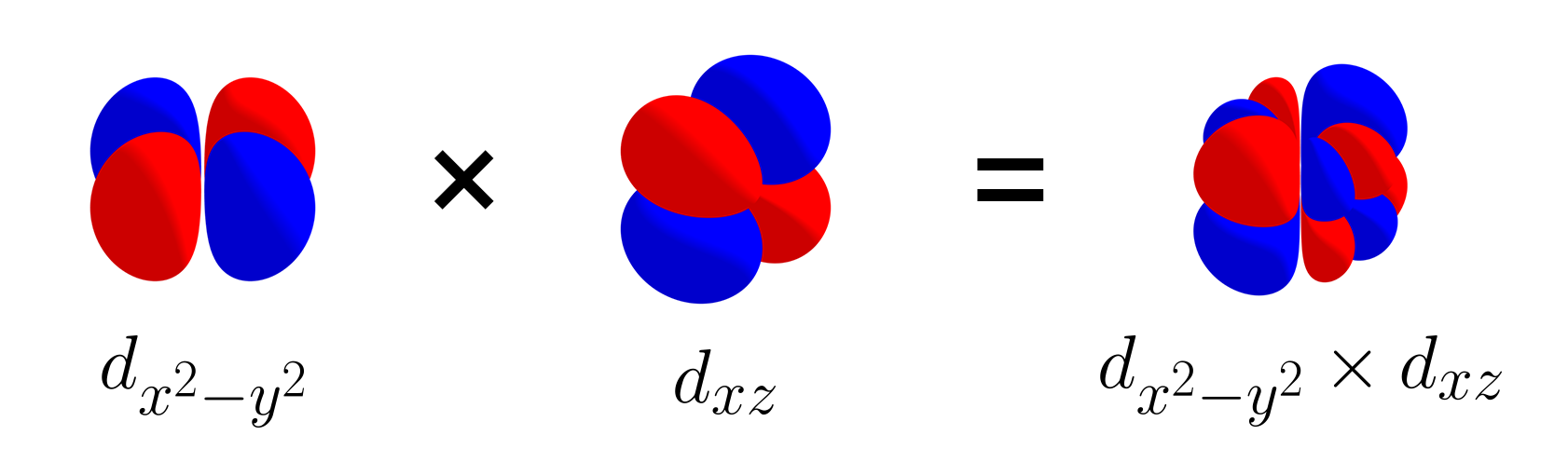

Likewise, the three $d$ orbitals are mutually orthogonal, and like the set of three p orbitals, this set is also linearly independent. Let’s add the $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ to the set and consider $\left\{d_{xy},\, d_{yz},\, d_{xz},\, d_{x^2 - y^2}\right\}$. $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ is orthogonal with $d_{xy}$, as shown with the picture below.

$d_{x^2 - y^2}$ is also orthogonal with $d_{xz}$ (as shown above), as well as $d_{yz}$ (not shown). As the orbitals of the set $\left\{d_{xy},\, d_{yz},\, d_{xz},\, d_{x^2 - y^2}\right\}$ are all mutually orthogonal, the set of four $d$ orbitals is also linearly independent.

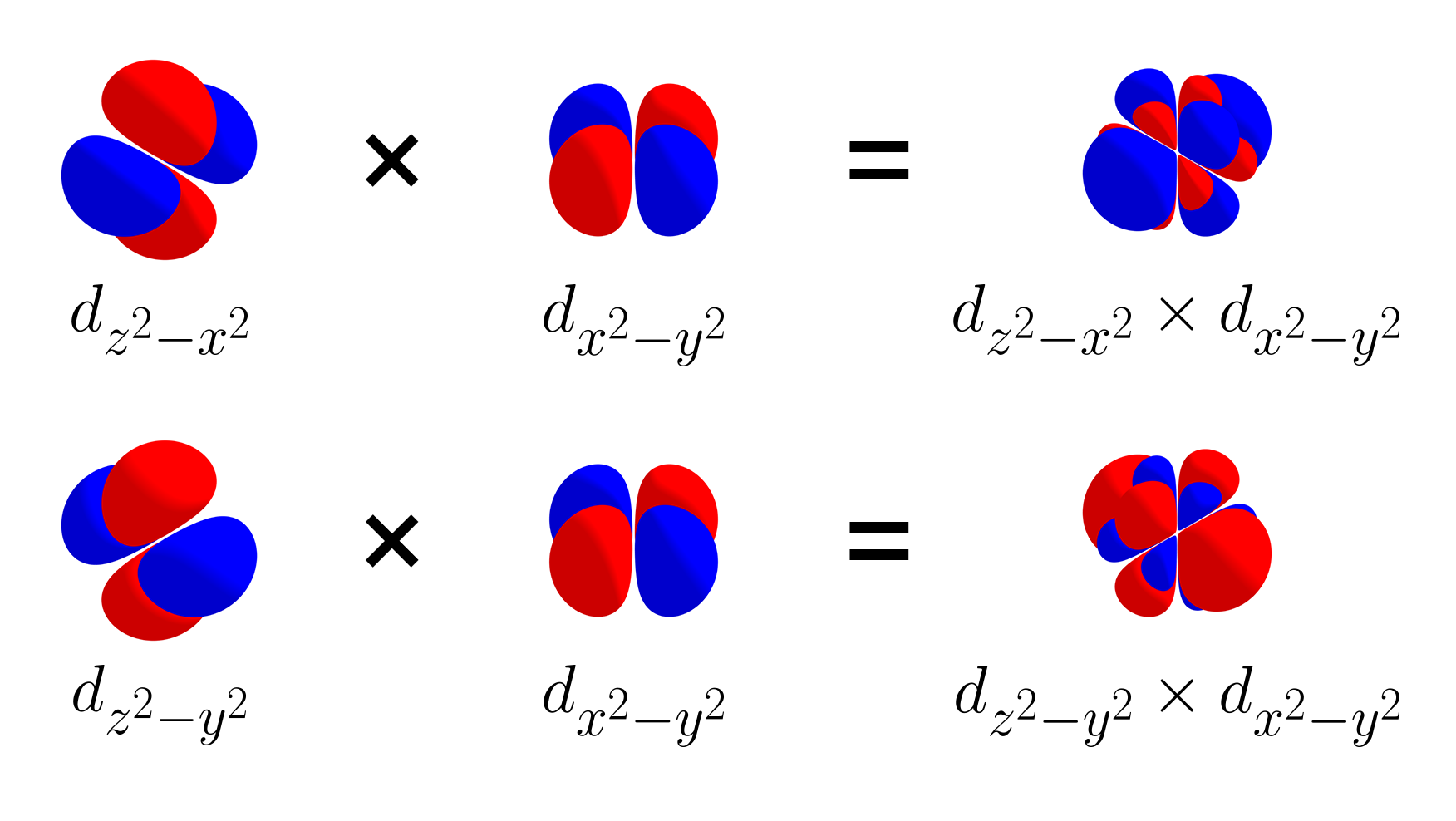

What happens if we add the $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ orbital and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ orbital to the set $\left\{d_{xy},\, d_{yz},\, d_{xz},\, d_{x^2 - y^2}\right\}$, resulting in a set of six $d$ orbitals $\left\{d_{xy},\, d_{yz},\, d_{xz},\, d_{x^2 - y^2},\, d_{z^2 - x^2},\, d_{z^2 - y^2}\right\}$? Like $d_{x^2 - y^2}$, the two new $d$ orbitals should be orthogonal to $d_{xy}$, $d_{yz}$, $d_{xz}$, and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$. Below is the product of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ and the product of $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$.

Unfortunately, the $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ orbitals are not orthogonal with $d_{x^2 - y^2}$. The product of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ has more negative lobes than positive lobes. The product of $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ has more positive lobes than negative lobes.

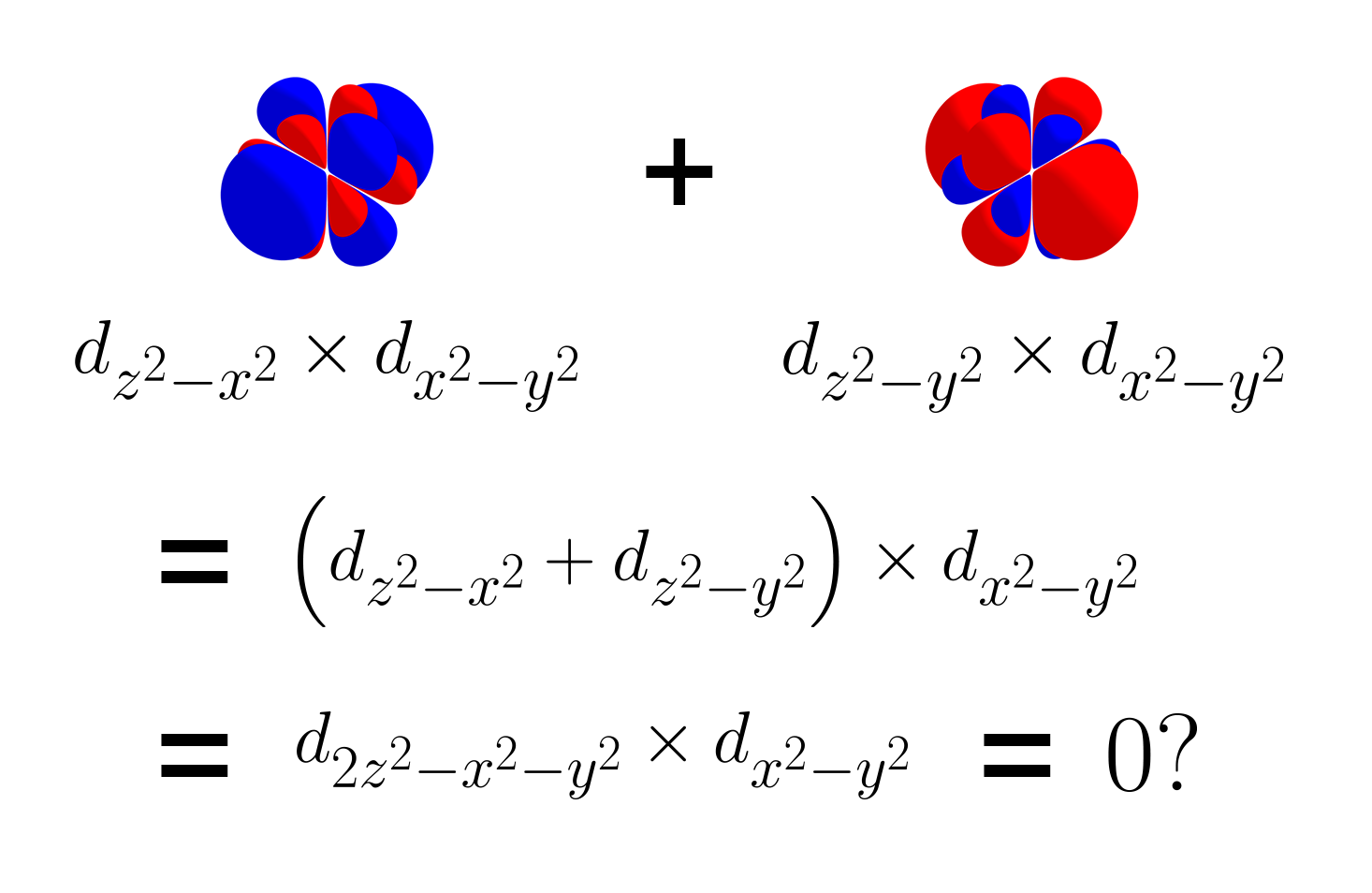

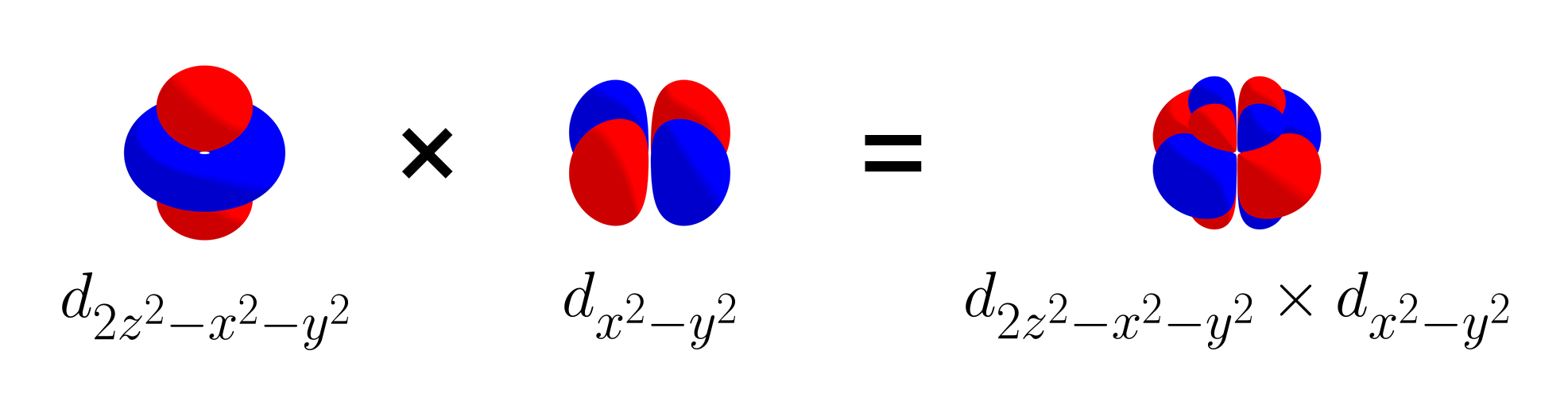

Looking closely, the two products are basically the same except for their sign. This could mean that the linear combination of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ by equal amounts are orthogonal to $d_{x^2 - y^2}$, because the positive parts and the negative parts may cancel out. To test this, below is the product between the sum of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ (thus $d_{2z^2 - x^2 - y^2}$) and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$.

Indeed, $d_{2z^2 - x^2 - y^2}$ and $d_{x^2 - y^2}$ are orthogonal, as their product has equal amounts of positive and negative parts. At this point, instead of labeling this new $d$ orbital $d_{2z^2 - x^2 - y^2}$, we call this new $d$ orbital $d_{z^2}$, as it has a similar symmetry as the function $f(x, y, z) = z^2$. For this reason, there are five d orbitals ($d_{xy}$, $d_{yz}$, $d_{xz}$, $d_{x^2 - y^2}$, $d_{z^2}$), instead of six $d$ orbitals.

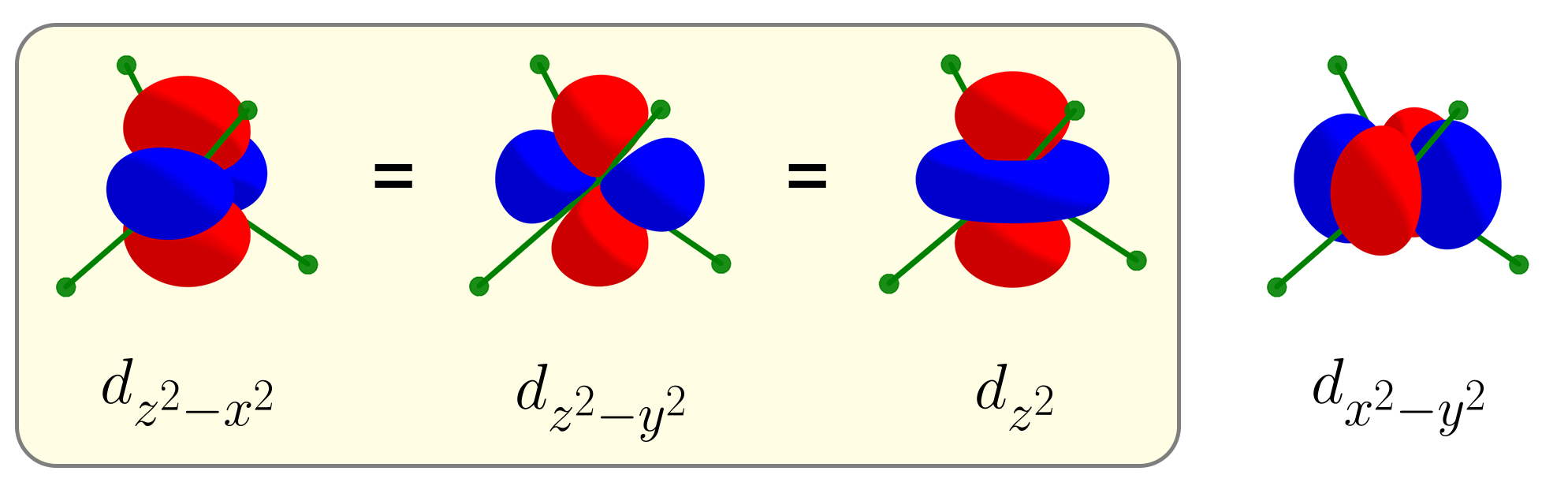

The exact way of obtaining $d_{z^2}$ is to sum $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$, then to normalize that sum to be equal to one like any other atomic orbitals. Due to this normalization, $d_{z^2}$ can be thought of as an average of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$. We’ll refer to this relationship between $d_{z^2}$, $d_{z^2 - x^2}$, and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ as an “average” rather than a “sum”. Here’s a small .gif image that shows that $d_{z^2}$ is the average of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$.

Application: Crystal Field Theory

The fact that the average of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$ is $d_{z^2}$ can be applied to intuitively understand the crystal field splitting patterns, without resorting to group theory.

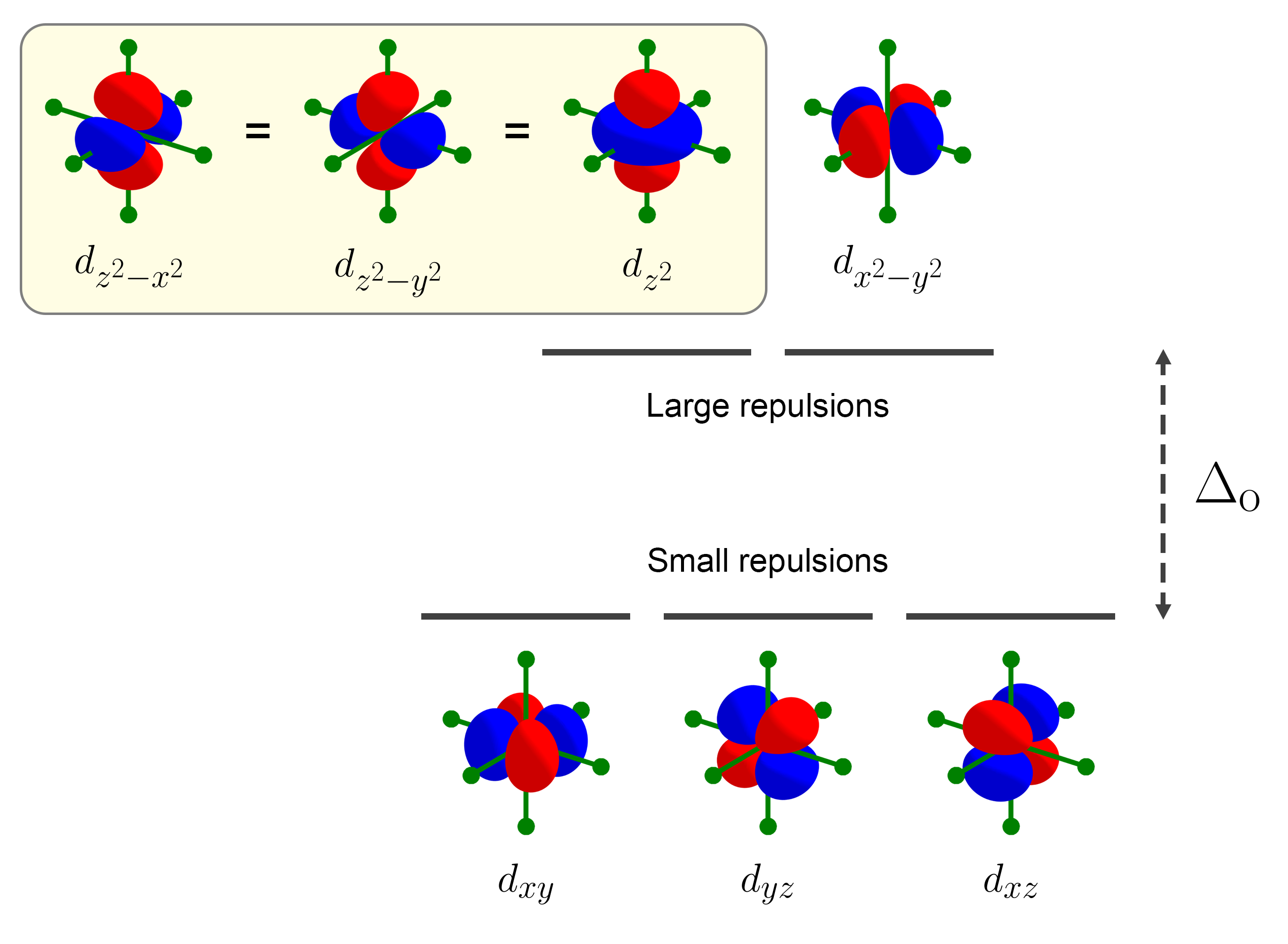

Let’s first look at octahedral splitting. There are two types of repulsions between ligands (denoted by green lines and circles) and the $d$ orbitals: small repulsions and large repulsions. For small repulsions, the $d$ orbitals are only weakly destablized by the ligands. $d$ orbitals that feel small repulsions are $d_{xy}$, $d_{yz}$, and $d_{xz}$ as shown below.

For large repulsions, the $d$ orbitals are strongly destablized by the ligands. By inspection, the $d$ orbitals (excluding $d_{z^2}$) that feel large repulsions are $d_{x^2 - y^2}$, $d_{z^2 - x^2}$, and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$, as four lobes of each $d$ orbital are directed towards the ligands. As the three $d$ orbitals experience the same amount of destablization, and as $d_{z^2}$ is the average of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$, $d_{z^2}$ also experience the same amount of destablization as the rest.

This results in the familiar $e_g$ and $t_{2g}$ octahedral splitting pattern.

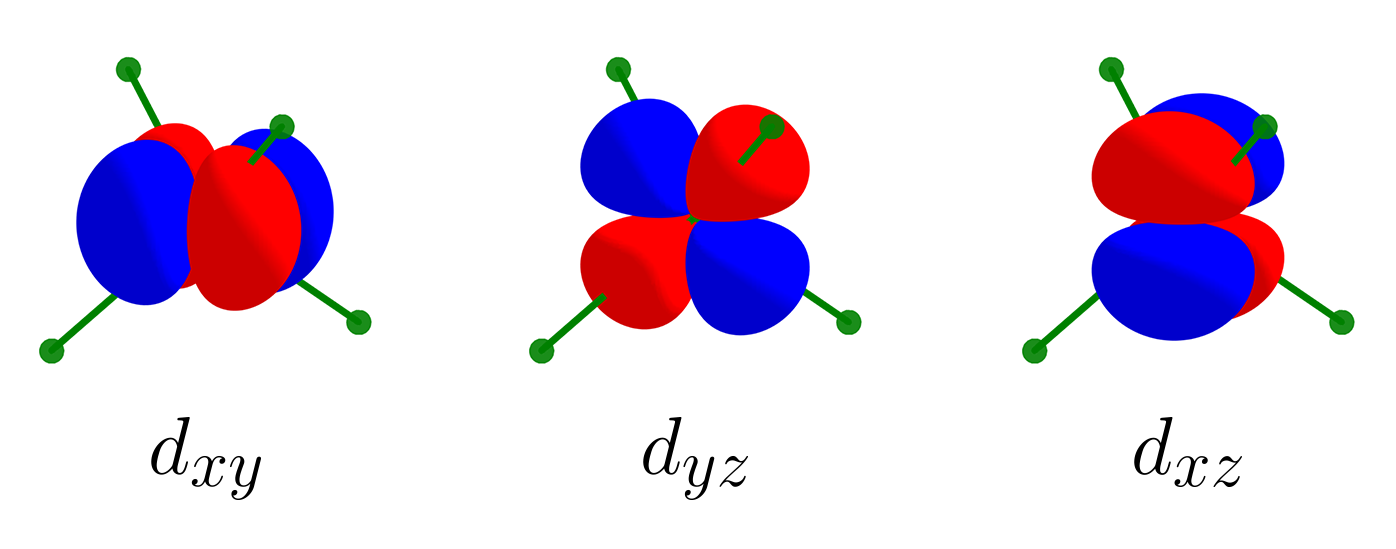

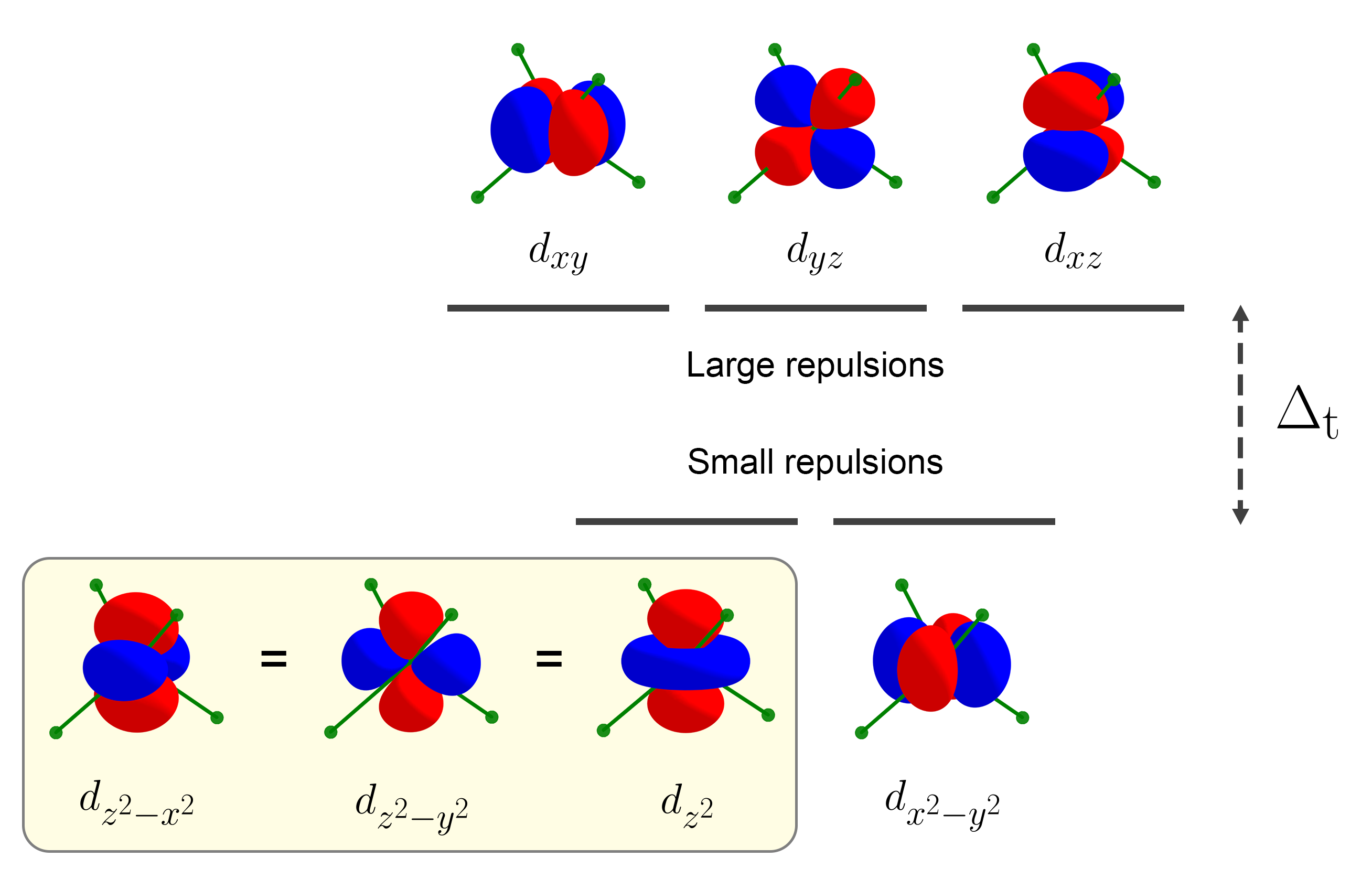

For tetrahedral splitting, the large repulsion cases are the same $d$ orbitals as the small repulsion cases of octahedral splitting. As shown below, the four lobes of each $d$ orbital is somewhat directed to the four ligands. Therefore, the $d$ orbitals that feel large repulsions are $d_{xy}$, $d_{yz}$, $d_{xz}$. As the lobes are directed at a 45 degree angle from the four ligands, tetrahedral splitting is smaller than octahedral splitting.

The $d$ orbitals with small repulsions are the same $d$ orbitals as the ones with large repulsions for octahedral splitting. Therefore, they are $d_{x^2 - y^2}$, $d_{z^2 - x^2}$, $d_{z^2 - y^2}$, and as a result, $d_{z^2}$.

This results in the inverted $t_{2g}$ and $e_g$ tetrahedral splitting pattern.

By knowing that $d_{z^2}$ is the average of $d_{z^2 - x^2}$ and $d_{z^2 - y^2}$, other splitting patterns can be easily derived without group theory.

Footnotes

-

Although orthogonality is not a requirement for linear independence, a set of mutually orthogonal vectors is always linearly independent. ↩

-

In reality, orbitals can be complex-valued functions. In this case, the orthogonality conditions is something like $\int_{\text{all space}} f^{*}\, g \,dV = 0$. ↩