A Different Approach for Molecular Orbitals of the Hydrogen Molecular Ion

Introduction

In the widely used textbook Principles of Modern Chemistry by David W. Oxtoby, the hydrogen molecular ion $\text{H}_2^+$ (HMI) is used as a bridge between atomic orbitals (AOs) and molecular orbitals (MOs). The textbook states that the wavefunction of the HMI can be solved exactly as it is a one-electron system1. It, however, does not actually solve the HMI and instead uses its results from someplace else. It then goes on about approximating MOs with the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbital method (LCAO), which is the main takeaway of the chapter.

I have always wondered how the HMI is exactly solved until recently. Now, with a new understanding of quantum mechanics and differential equations, I set out to tackle this long-anticipated question. Thankfully, with some papers and resources on obtaining a very accurate solution for the HMI, I was able to approximately calculate the wavefunctions for the HMI with the Jupyter Notebooks in my GitHub repo, hydrogen-molecular-ion.

I intend to share some of my findings during this journey, without the complicated mathematics and physics involved. Although this may be entirely useless from a chemistry education standpoint, it nevertheless will be interesting to those who have had the same questions as me.

Housekeeping

As the HMI is at the atomic scale, it is a good idea to use atomic units - units for length and energy for our purposes. They are the Bohr radius $a_0$, which is equal to $5.29 \times 10^{-11} \text{ m}$, and the Hartree $E_h$, which equal to $27.2 \text { eV}$. The Hartree is useful as it is also equal to twice the absolute value of the energy of a ground state hydrogen.

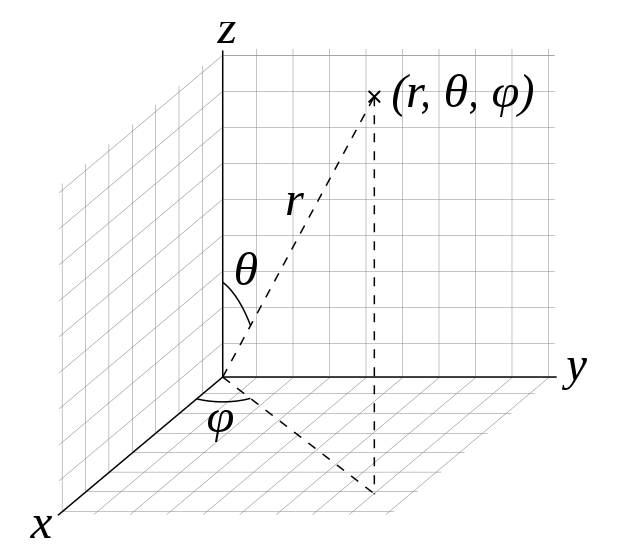

Now is a good time to remind ourselves of the spherical coordinate system, which is essential when solving the Schrödinger equation for hydrogen. The spherical coordinates $r$, $\theta$, and $\phi$ are defined as follows, with their bounds being $0 \leq r\, ,\; 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi\, ,\; 0 \leq \phi < 2\pi$.

Why is the spherical coordinate system used for hydrogen? That is because the hydrogen system is spherically symmetric. More specifically, the Hamiltonian for the Schrödinger equation for hydrogen is (in atomic units)

\[\hat{H}=-\frac{1}{2}\nabla^{2}-\frac{1}{r}\]which is dependent and only dependent on $r$: thus, the spherical symmetry.

We are now ready for the HMI.

A Different Way of Thinking About HMI

The HMI is not too different from the case of hydrogen; instead of having one proton and one electron, we now have two protons and one electron. The distance between the two protons - called equilibrium internuclear distance - is found to be approximately $2.0 \; a_0$.

Now consider the following.

Imagine a stable Helium-2 $ \; { }^{2}\text{He}^{+}$ ion with a single electron. Initially, the wavefunction of the electron is one of the typical hydrogen-like atomic orbitals.

As you forcefully tear the two protons of the nucleus apart, the electron wavefunction slowly distorts to reflect the changing system. When the two protons are separated by a distance of $ \; 2.0 \; a_0$, the electron wave function is that of the familiar HMI treated in physical/quantum chemistry textbooks.

At last, as the two protons continue to be separated, this system now closely resembles that of the infinitely separated proton and a neutral hydrogen atom (again, think of hydrogen atomic orbitals).

Let us dive deeper in this line of thought. At first, the HMI resembles that of $^{2}\text{He}^{+}$, which, again, is the typical hydrogen-like atom. Solved practically the same way as that of hydrogen, but with nuclear charge $Z = 2$. This is called the united-atom limit.

On the other extreme end, the HMI has two protons, which are infinitely separated, and an electron, technically bound to either proton. As the two protons are identical, the wavefunction of this HMI is the sum of one hydrogen atomic orbital at one proton and another hydrogen atomic orbital at the other proton. This limit, called the separated-atoms limit, is the limit where the LCAO-MO approaches the exact MO.

What we must recognize is that this is continuous - the wavefunction of the united-atom limit gradually morphs into the wavefunction of the separated-atoms limit. Below is a table of such correlations.

Changes in the Coordinate System

Before we deal with the MOs, let us first think about the coordinate system. As the internuclear distance starts from zero and then increase, the system is no longer spherically symmetric. Thus, we must resort to a newer coordinate system that better reflects the altered symmetry.

The natural symmetry that arises is the prolate spheroidal (an ellipse spun around the major axis) symmetry, with the foci of the prolate spheroid on the two nuclei. To exploit this new symmetry, we use the prolate spheroidal coordinate system, which we will shorten it to ‘spheroidal coordinates’.

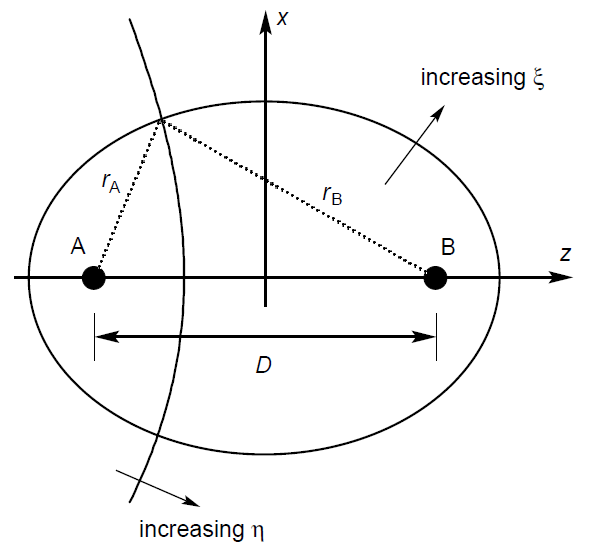

For spheroidal coordinates, we let $D$ be the internuclear distance, and we set the origin to be its midpoint. The internuclear bonding axis is set as the z-axis, and the x and y-axes are set accordingly.

The distance between nuclei A (located at $(0, 0, -\frac{D}{2})$) is denoted as $r_A$, and the distance between nuclei B (located at $(0, 0, +\frac{D}{2})$) is denoted as $r_B$.

We introduce three coordinates, $\xi$, $\eta$, and $\phi$ (same as the $\phi$ of the hydrogen atom).

\[\xi = \frac{r_A+r_B}{D} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad 1 \leq \xi\] \[\eta = \frac{r_A-r_B}{D} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad \; -1 \leq \eta \leq +1\] \[\phi = \tan^{-1}\left ( \frac{y}{x} \right ) \text{, usually defined to be } 0 \leq \phi < 2\pi\]The surface formed by fixing various coordinates can be deduced from the definition of certain conic sections. Fixing $\xi$ and varying the other coordinates yields a prolate spheroid (an ellipse spun around the major axis). Fixing $\eta$ and varying the other coordinates forms one half of a two-sheet hyperboloid (half of a hyperbola spun around the major axis).

We will not do any advanced mathematics with spheroidal coordinates. The reason spheroidal coordinates were introduced is to demonstrate how the coordinate system morphs from the united-atom limit to the separated-atoms limit.

As $D \to 0$, $\frac{1}{2}D \xi = \frac{1}{2} \left ( r_A + r_B \right )$ approaches $r$ of spherical coordinates. Therefore, the prolate spheroid formed by fixing $\xi$ is now a sphere, formed by fixing $r$. Similarly, as $D \to 0$, the hyperboloid formed by fixing $\eta$ is now a cone, formed by fixing $\eta$.

For spherical coordinates, we have spherical harmonics. For prolate spheroidal coordinates, we have the prolate spheroidal harmonics. Whereas the wavefunction of the united-atom limit are based on spherical harmonics, the wavefunction of $D > 0$ are based on prolate spheroidal harmonics. As $D \to 0$, prolate spheroidal harmonics converge to spherical harmonics.

Unlike spherical harmonics, prolate spheroidal harmonics are difficult to solve. This is why the actual process of obtaining MOs for the HMI is not covered in the aforementioned textbook.

The Molecular Orbitals Themselves

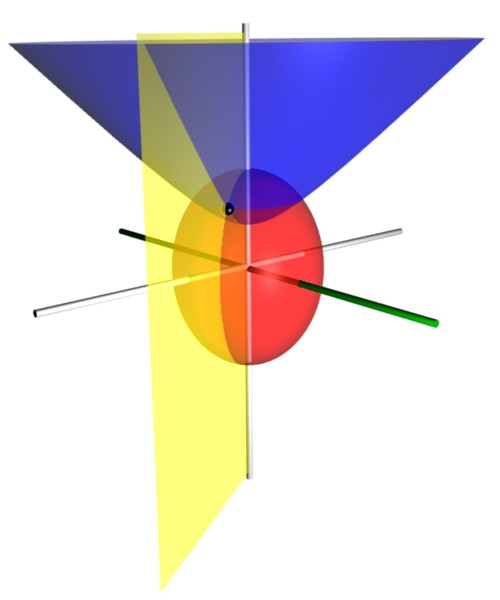

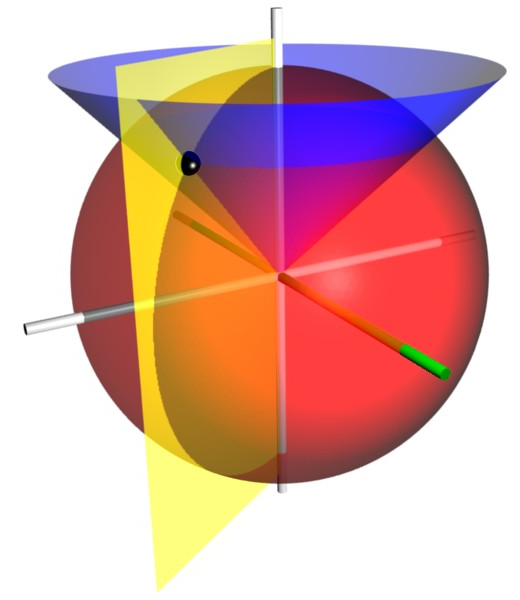

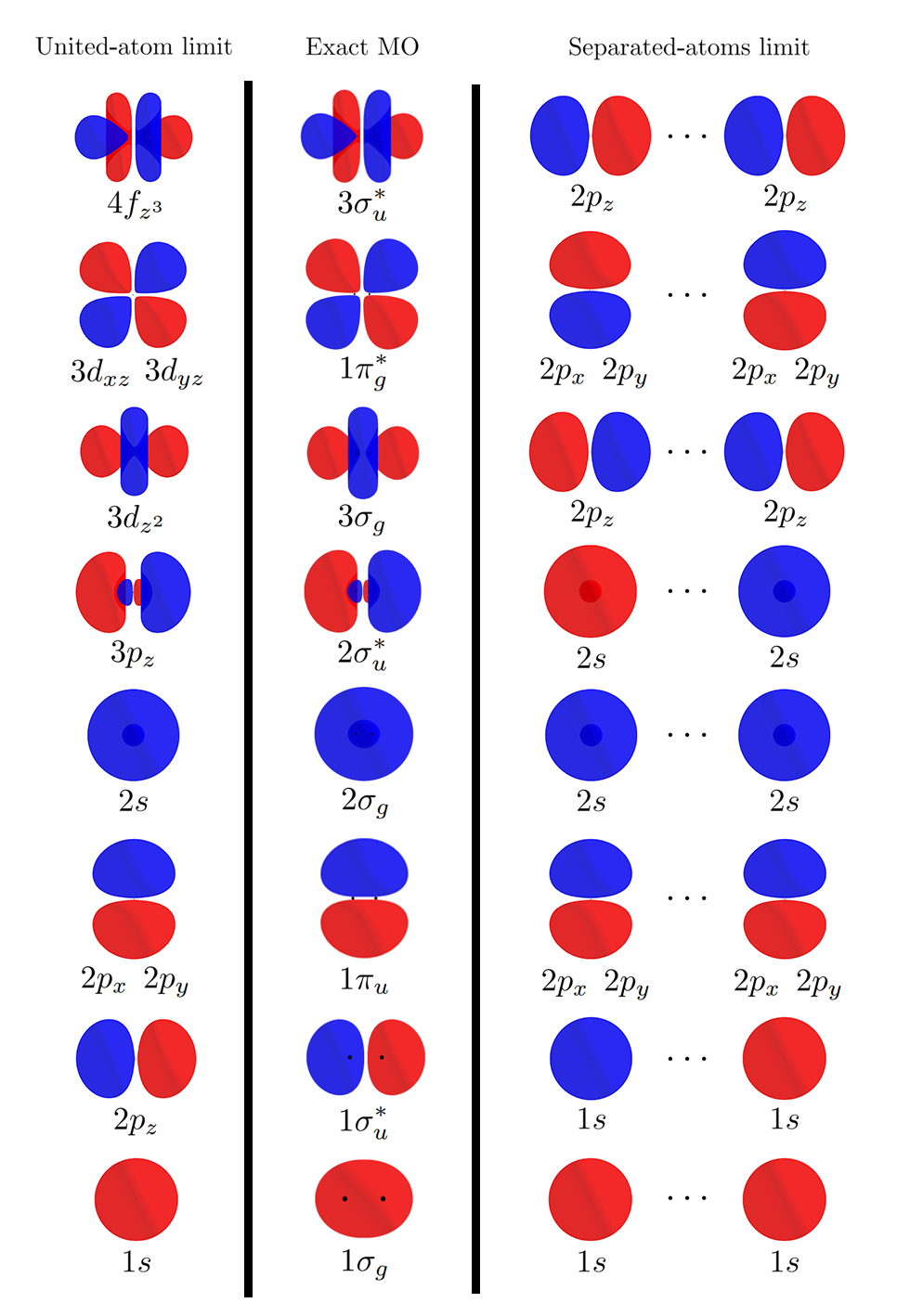

Coming back to the MOs themselves, below is a graphical representation of how MOs morph from the united-atom limit to the separated-atoms limit2 (Note: orbitals not to scale).

There are two things to note. First, notice how similar the MOs of the united-atom limit is to the actual MOs (with $D = 2.0$). Second, the MOs of the separated-atom limit is the exact same as the combination of AOs used for obtaining LCAO-MOs.

Now Thinking with Graphs

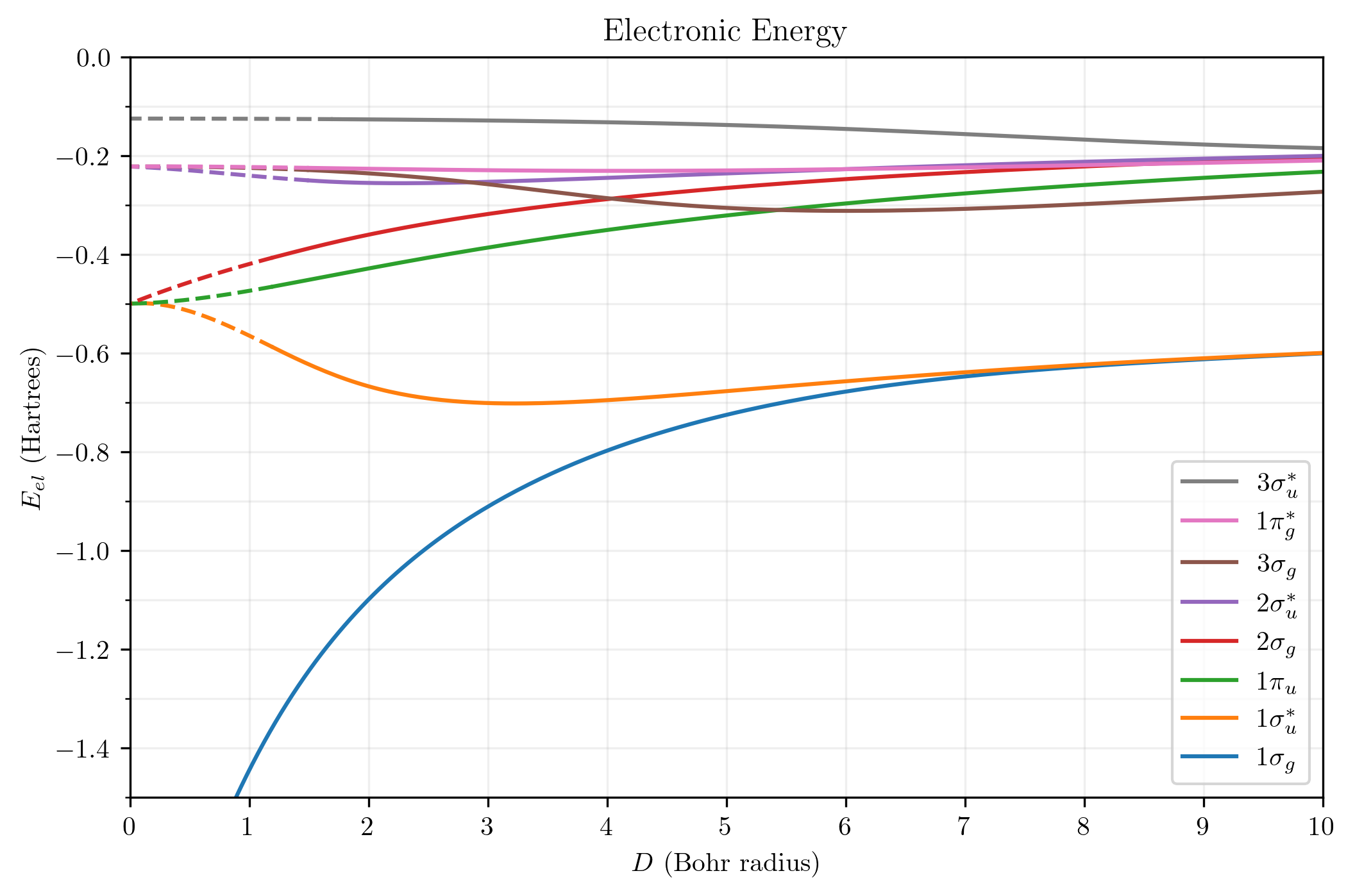

When the internuclear distance changes and the wavefunction of the HMI morphs accordingly, their energies also change. Let us investigate the electronic energy - total energy except repulsion between the two nuclei.

The graph kind of is a mess, but there are three points to be made:

A. At the united-atom limit $(D=0)$, the electronic energy converges to that of hydrogen-like AOs with $Z=2$: $E_{el} = -Z^2 / \left ( 2 n^2 \right ) = -2/n^2$.

B. At the separated-atoms limit, the electronic energy converges to the average of those of the hydrogen-like AOs. The two lowest states converge to

\[E_{el} = \frac{ -\frac{1}{2} + -\frac{1}{2}}{2} = -\frac{1}{2}\]and the remaining states converge to

\[E_{el} = \frac{ -\frac{1}{8} + -\frac{1}{8}}{2} = -\frac{1}{8}\]In hindsight, these two points could have been predicted from our initial observations about the MOs.

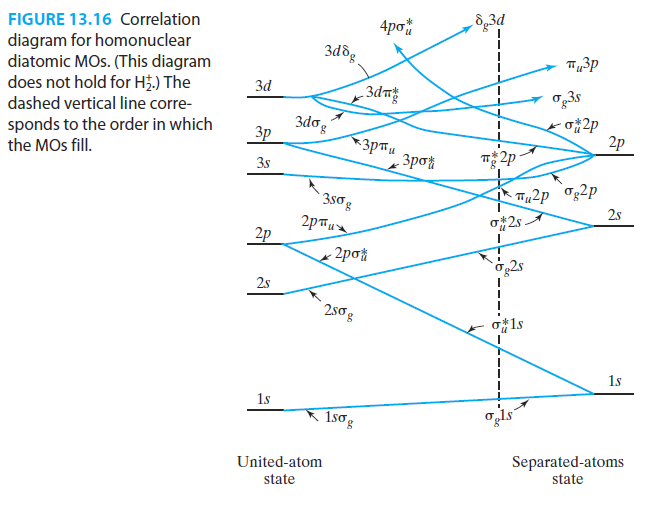

C. The order of the MOs is quite unpredictable. This is also the case for multielectron homonuclear diatomic MOs.

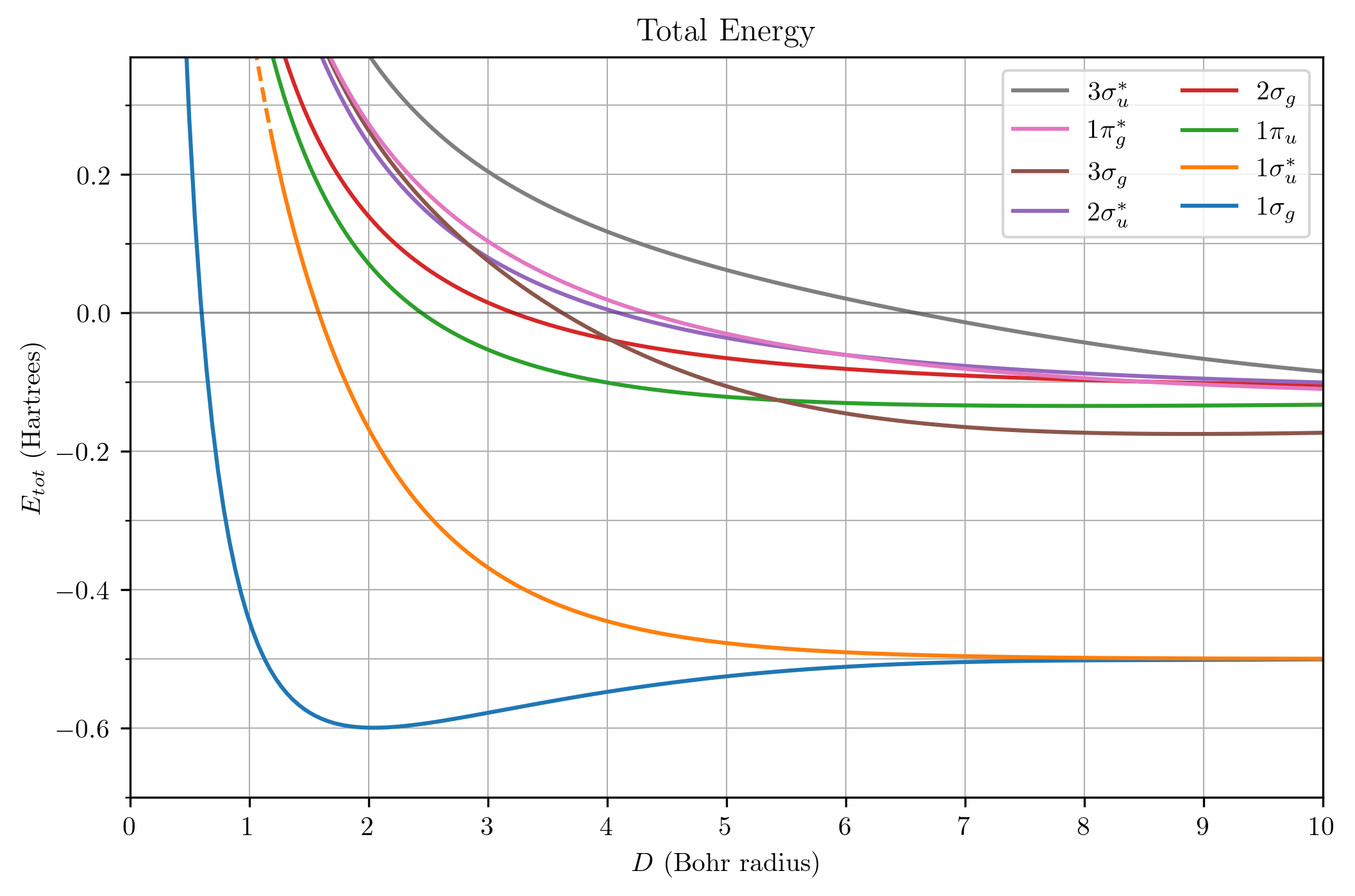

Here is the total energy graph for good measure.

Conclusion

The MOs for the HMI can be thought of as extensions of the AOs of hydrogen-like atoms.