A (More or Less) Complete Explanation on s-p Mixing

A Quick Review on LCAO

The molecular orbitals (MOs) of homonuclear diatomic molecules can be constructed with the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbital method (LCAO). Let’s take $\text{O}_2$ as an example.

First, the $1s$ orbitals of each fluorine atom contribute very little to bonding as they hardly overlap.

Thus, we will ignore the $1s$ orbitals and only consider the $2s$ and $2p$ orbitals.

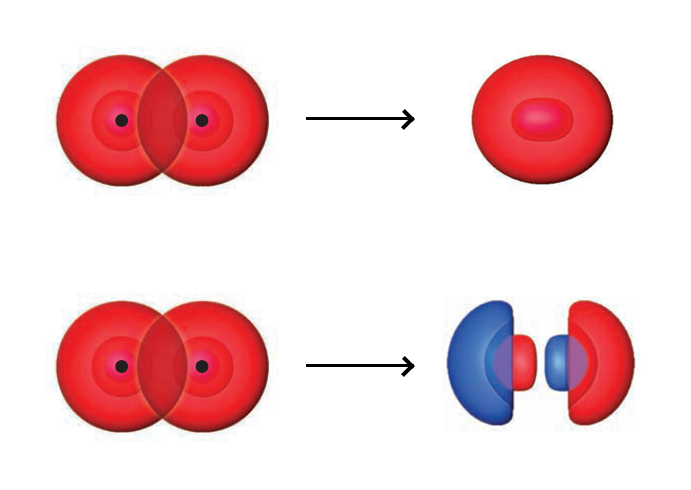

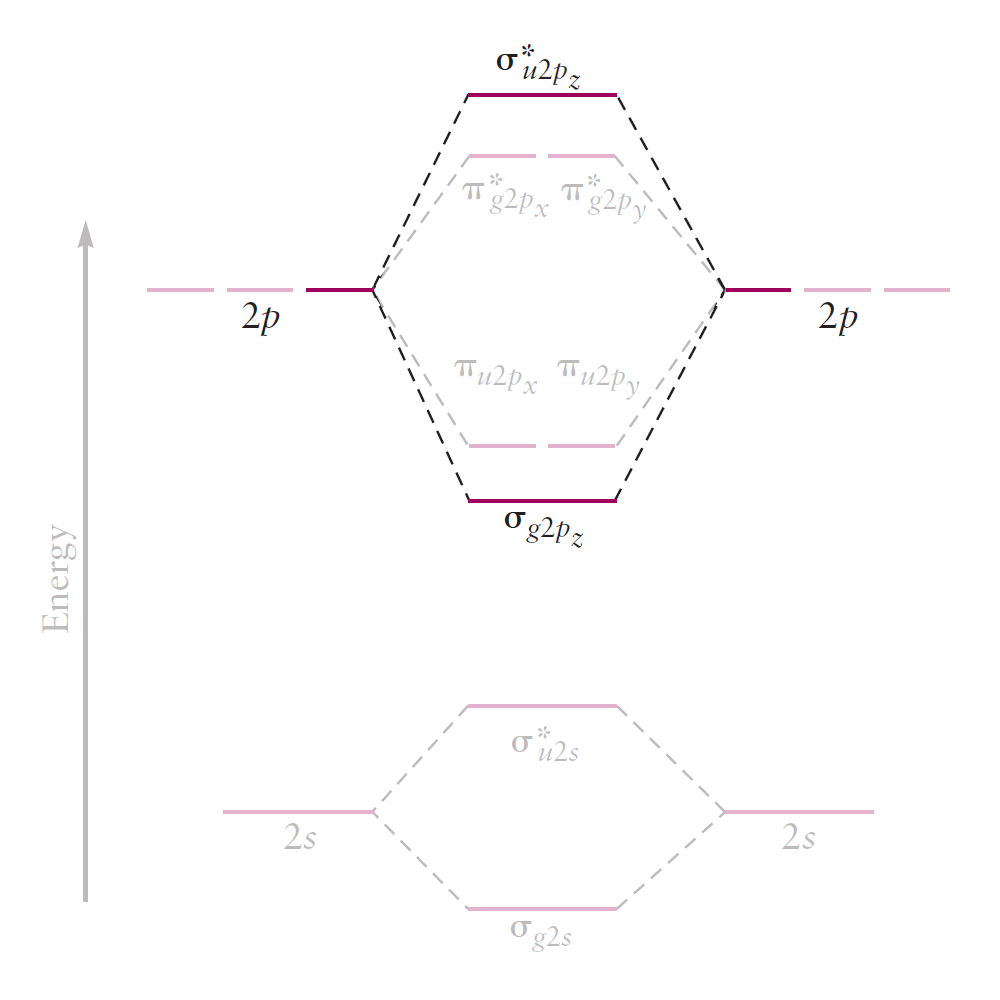

For the $2s$ orbitals, the $2s$ orbitals can form either a bonding MO $(\sigma _{g2s})$ or an antibonding MO $(\sigma _{u2s}^\ast)$.

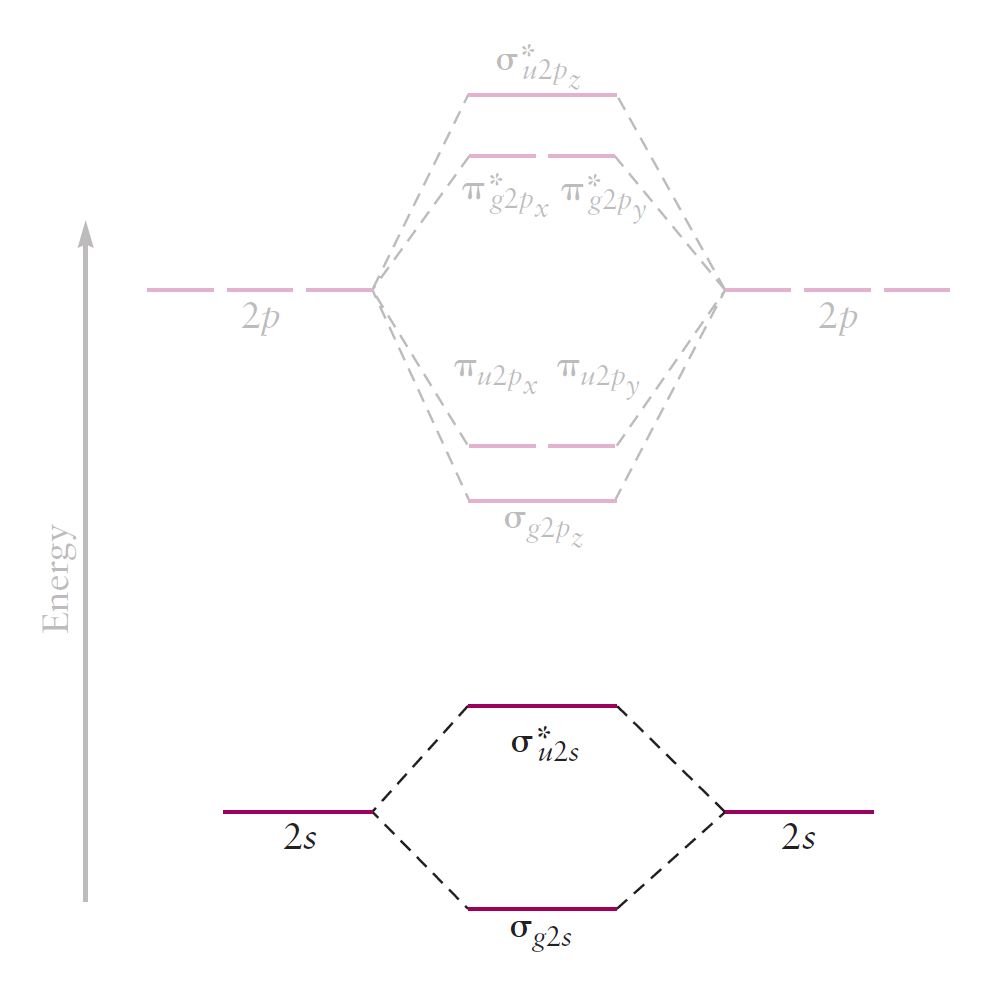

The resulting correlation diagram is as follows.

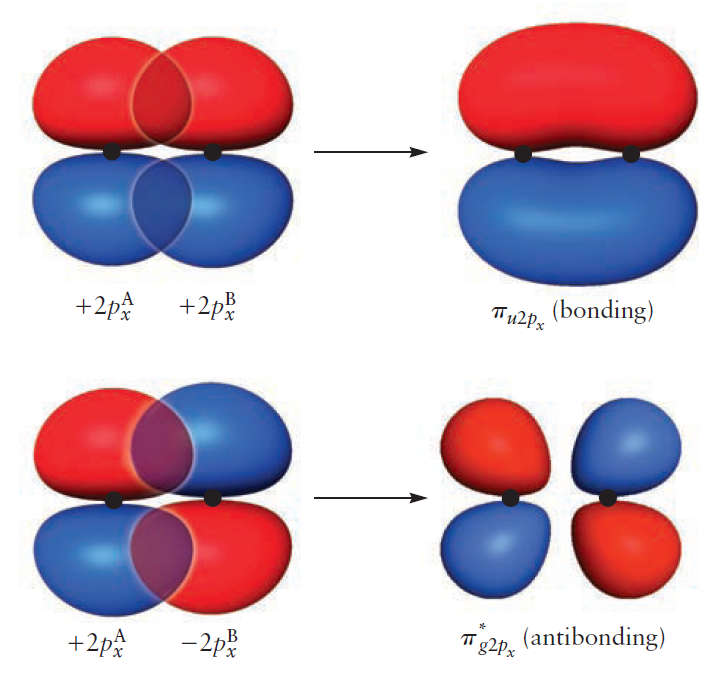

$2p_{x}$ orbitals overlap side-by-side to form either the bonding MO $\pi_{u2p_{x}}$ or the antibonding MO $\pi_{g2p_{x}} ^{\ast}$. The same is true for $2p_{y}$ orbitals, resulting in the formation of bonding MO $\pi_{u2p_{y}}$ and antibonding MO $\pi_{g2p_{y}} ^{\ast}$.

The resulting correlation diagram is as follows.

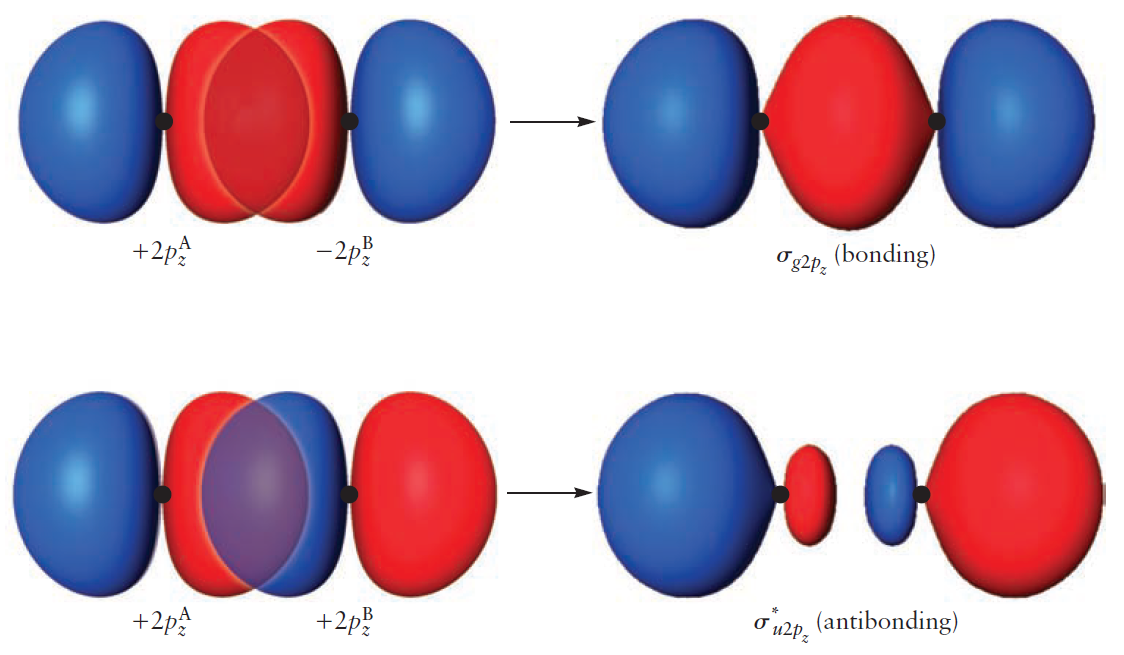

Lastly, the $2p_z$ orbitals overlap end-on to form either a bonding MO $(\sigma _{g2p_z})$ or an antibonding MO $(\sigma _{u2p_z}^{\ast})$.

Because the overlap between AOs is large, the energy split between the two MOs is larger than before.

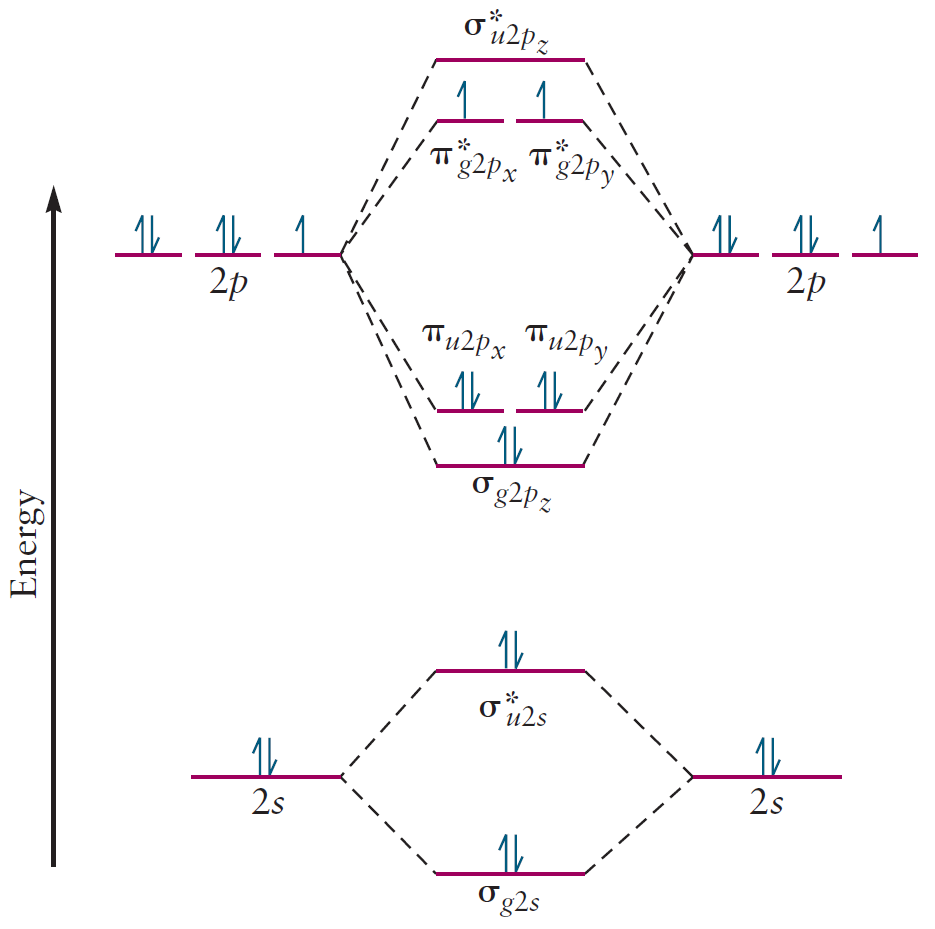

After filling in the MOs with electrons according to the Aufbau principle, the correlation diagram is complete. Note the unpaired electrons which cause $\text{O}_2$ to be paramagnetic.

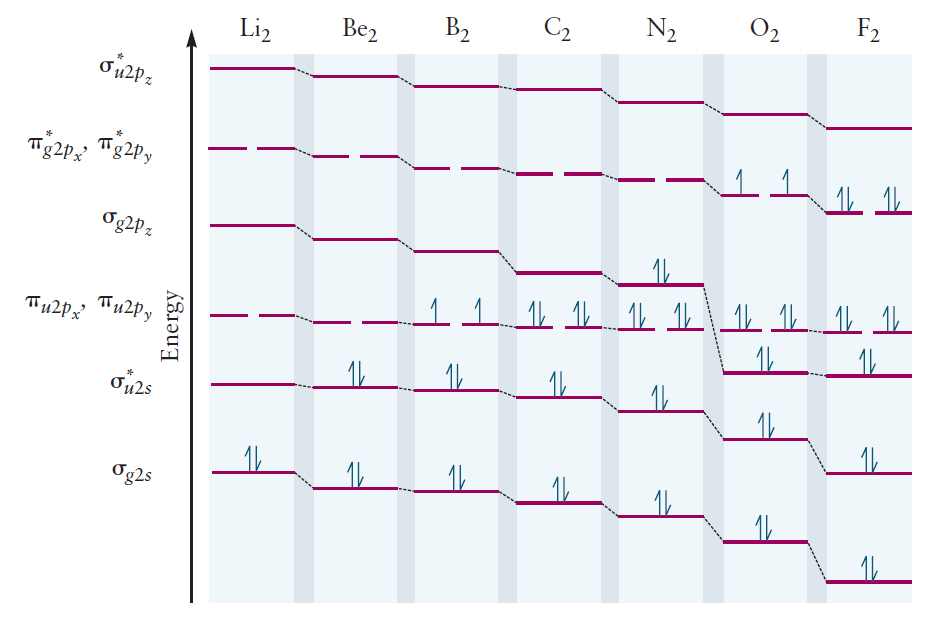

The correlation diagram of $\text{F}_2$ is similar. However, for other second-period elements $(\text{Li}$ to $\text{N})$, the order among $\pi _{u2p_x} / \pi _{u2p_y}$ and $\sigma _{g2p_z}$ is reversed: the energy of $\pi _{u2p_x} / \pi _{u2p_y}$ is nearly constant, but the energy of $\sigma _{g2p_z}$ is raised considerably.

Most introductory textbooks on chemistry attribute this to s-p mixing: the mixing of $2s$ and $2p_z$, due to their small difference in energy. Although this explanation is correct, it is certainly inadequate. It is the purpose of this article is to explain this anomaly in a way that is complete, and most of all, satisfying.

The Criteria for Orbital Mixing - Revisited

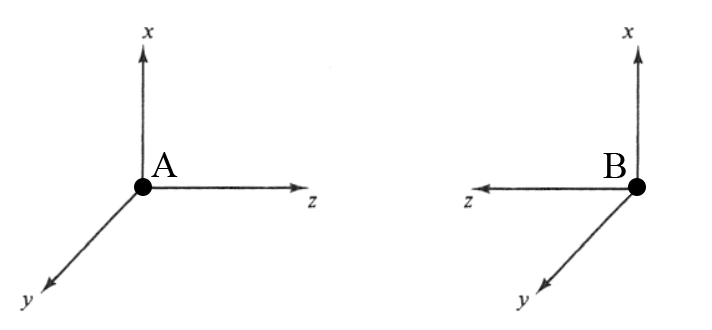

Before we begin, let us clear up some convention used in this article. The two nuclei are called A and B, with their coordinate systems arranged as shown below.

Note how the local coordinate system for nucleus B is left-handed, instead of the usual right-handed system like that of nucleus A. This is done so that the addition of AOs in constructive interference, while the subtraction of one AO from the other results in destructive interference.

In simpler terms, addition results in bonding MOs and subtraction results in antibonding MOs.

We must first return to the principles of LCAO. Technically speaking, when constructing any molecular orbital, we can use as much atomic orbitals as we want.

\[\Psi = c_{1}\psi _{1s \vert \text{A}} + c_{2}\psi _{1s \vert \text{B}} + c_{3}\psi _{2s \vert \text{A}} + c_{4}\psi _{2s \vert \text{B}} + c_{5}\psi _{2p_{\text{z}} \vert \text{A}} + c_{6}\psi _{2p_{\text{z}} \vert \text{B}} + \cdots\]In a slightly more legible notation:

\[\Psi = c_{1}1s^{\text{A}} + c_{2}1s^{\text{B}} + c_{3}2s^{\text{A}} + c_{4}2s^{\text{B}} + c_{5}2p_{z}^{\text{A}} + c_{6}2p_{z}^{\text{B}} + \cdots\]In fact, as we use more atomic orbitals, we get better and better results. However, using too many atomic orbitals is problematic for these two reasons.

- It becomes harder to solve, let alone understand.

- It is overkill for obtaining approximate/qualitative solutions.

Therefore, we try to work with the smallest number of AOs at a time - just enough to construct the roughly correct MOs and their energies1. Two criteria - derived from advanced quantum calculations - are helpful in this regard.

A. Significant Overlap

The first criterion is that in order for AOs to mix2, they must have overlap significantly. For example, consider $2s^A$ and $2p_x^B$ orbitals.

$2s^A$ and $2p_x^B$ do not mix well because (A) there is little overlap, and (B) there is roughly the same amount of constructive and destructive interference, which leads to neither bonding nor antibonding. From this, we can safely ignore the mixing of those two orbitals.

To elaborate on this point, only the AOs with the right axial symmetry is considered when mixing.

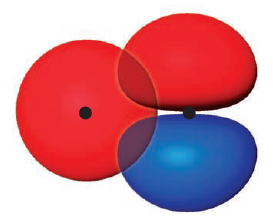

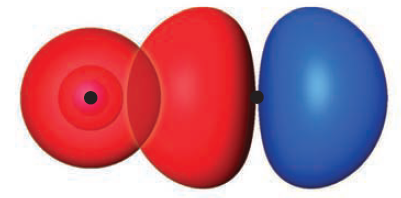

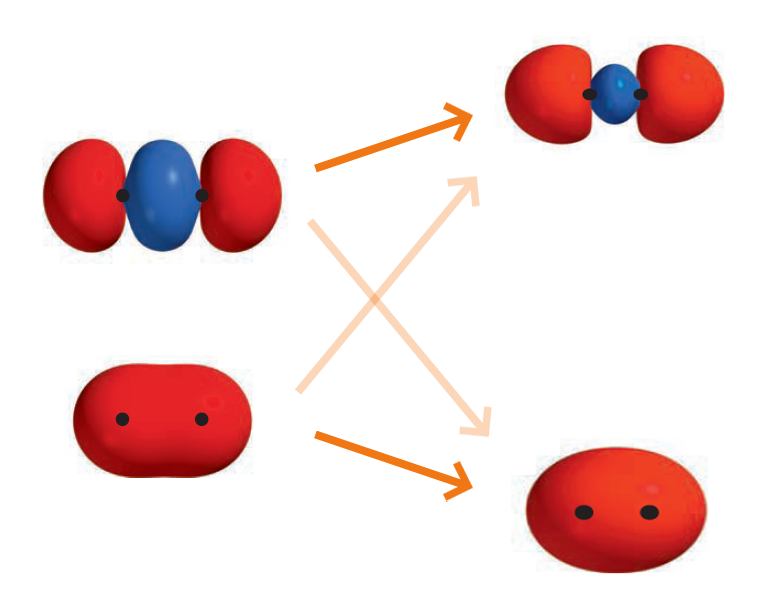

First, we deal with AOs (not MOs) of $\sigma$ symmetry - invariant under any rotation about the internuclear axis. They consist of $1s$, $2s$, and $2p_z$, and these AOs linearly combine to form $\sigma$ MOs. Below is an example with $2s^A$ and $2p_z^B$.

Second, we turn our attention to AOs of $\pi$ symmetry - which reverse phase under $180^{\circ}$ rotation. Consisting of $2p_x$ and $2p_y$, $2p_x^A$ mixes with $2p_x^B$ and $2p_y^A$ mixes with $2p_y^B$ to form the $\pi$ MOs.

B. Similar Energy Level

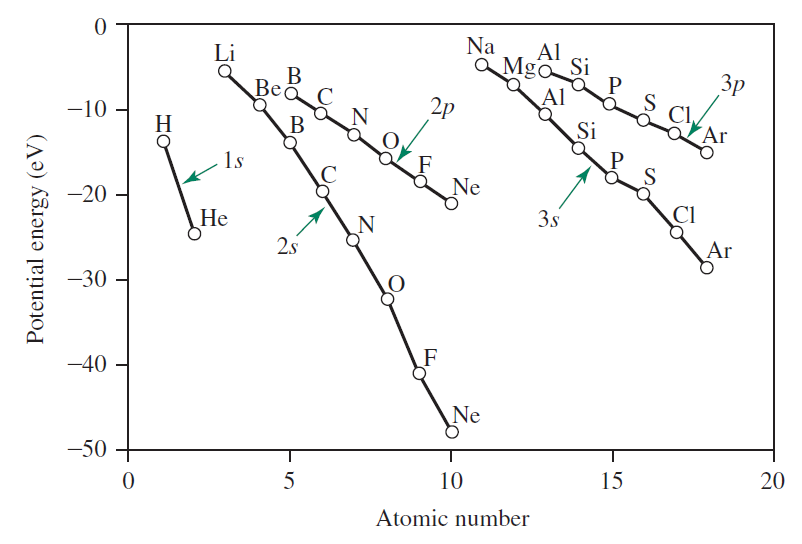

The second criterion requires AOs of similar energy for mixing. In general, AOs with energy difference greater than $10 \sim 14 \text{ eV}$ do not mix. Below is a graph of energy of $2s$ and $2p$ orbitals.

Going back to the AOs of $\sigma$ symmetry ($1s$, $2s$, and $2p_z$), it is clear that the energy difference between $1s$ and $2s$ / $2p_z$ is very large - much larger than the $10 \sim 14 \text{ eV}$ threshold. We can now safely ignore the $1s$ orbitals when constructing MOs.

However, the energy difference between $2s$ and $2p_z$ is unclear and requires our attention. Below is the calculation of the energy difference between the two AOs for some second-period elements.

| Element | Energy of $2s$ ($\text{eV}$) | Energy of $2p$ ($\text{eV}$) | Difference in Energy ($\text{eV}$) | Mixing between $2s$ and $2p_z$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\text{C}$ | -19.43 | -10.66 | 8.77 | Yes |

| $\text{N}$ | -25.56 | -13.18 | 12.38 | Yes |

| $\text{O}$ | -32.38 | -15.85 | 16.53 | No |

| $\text{F}$ | -40.17 | -18.65 | 21.52 | No |

It seems that mixing between $2s$ and $2p_z$ occurs for elements $\text{N}$3 and earlier. This is the s-p mixing that was previously mentioned.

Thus, for $ \text{Li}_ 2 \sim \text{N}_ 2 $, to construct the two bonding $\sigma_g$ MOs (substitutes for the original $\sigma_{g2s}$ and $\sigma_{u2p_{z}}$), we use the following LCAO instead.

\[\Psi = c_{1}2s^{\text{A}} + c_{1}2s^{\text{B}} + c_{2}2p_{z}^{\text{A}} + c_{2}2p_{z}^{\text{B}}\]For the two antibonding $\sigma_u^{\ast}$ MOs (substitutes for the original $\sigma_{g2s}$ and $\sigma_{u2p_{z}}$), we use the following LCAO instead.

\[\Psi = c_{3}2s^{\text{A}} - c_{3}2s^{\text{B}} + c_{4}2p_{z}^{\text{A}} - c_{4}2p_{z}^{\text{B}}\]In total, four MOs were constructed from four AOs. This is the most important takeaway of this article: more than one pair of AOs can be used to construct more than one pair of MOs.

Anyway, note that the coefficients $c_1 \sim c_4$ are all positive. The coefficients are shared between the same kind of orbitals as we are dealing with the homonuclear case. In other words, we see equal contribution from the same kind of orbitals from each atom.

The coefficients $c_1 \sim c_4$ can be calculated through some quantum calculation, and indeed the energy of $\sigma_{g2p_z}$ will be higher than that of $\pi_{u2p_x}$ and $\pi_{u2p_y}$. Case closed.

This conclusion should definitely irk you. Couldn’t there be a better, more tangible explanation?

Mixing Molecular Orbitals Instead of Atomic Orbitals

We’ve seen how atomic orbitals mix. Now is the time to mix molecular orbitals. Instead of mixing $2s$ and $2p_z$ orbitals, what if we mixed the ‘four original LCAO-MOs’ to obtain ‘four newer and better MOs’? (they will be designated as ‘improved’ to avoid confusion)

The four original LCAO-MOs are as follows ($a_{1} \sim a_{4}$ are normalization constants).

\[\sigma_{g2s} = a_{1} \left ( 2s^{\text{A}} + 2s^{\text{B}} \right ) \qquad \sigma_{u2s}^{\ast} = a_{2} \left ( 2s^{\text{A}} - 2s^{\text{B}} \right )\] \[\sigma_{g2p_z} = a_{3} \left ( 2p_{z}^{\text{A}} + 2p_{z}^{\text{B}} \right ) \qquad \sigma_{u2p_{z}}^{\ast} = a_{4} \left ( 2p_{z}^{\text{A}} - 2p_{z}^{\text{B}} \right )\]By mixing the two $\sigma_g$ MOs, we obtain two new $\sigma_{g \, \vert \, \text{improved}}$ MOs: $\sigma_{g2s \, \vert \, \text{improved}}$ and $\sigma_{g2p_{z} \vert \, \text{improved}}$

\[\Psi = c_{1}2s^{\text{A}} + c_{1}2s^{\text{B}} + c_{2}2p_{z}^{\text{A}} + c_{2}2p_{z}^{\text{B}} = c_{1} \left ( 2s^{\text{A}} + 2s^{\text{B}} \right) + c_{2} \left (2p_{z}^{\text{A}} + 2p_{z}^{\text{B}} \right )\] \[\therefore \Psi = \tilde{c_1} \sigma_{g2s} + \tilde{c_2} \sigma_{g2p_z}\]where $\tilde{c_1} = a_1 / c_1, \tilde{c_2} = a_2 / c_2$.

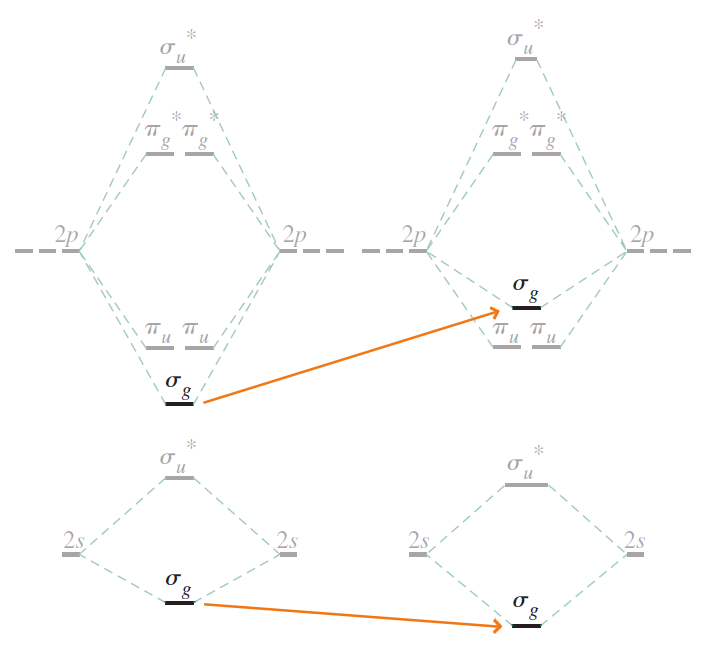

With $\sigma_{g2s}$ as the baseline, the electron density of $\sigma_{g2s \, \vert \, \text{improved}}$ between the two nuclei is significantly larger. This in turn stabilizes the MO.

On the other hand, compared to $\sigma_{g2p_{z}}$, the electron density of $\sigma_{g2p_{z} \vert \, \text{improved}}$ between the two nuclei is significantly smaller. This in turn destabilizes the MO.

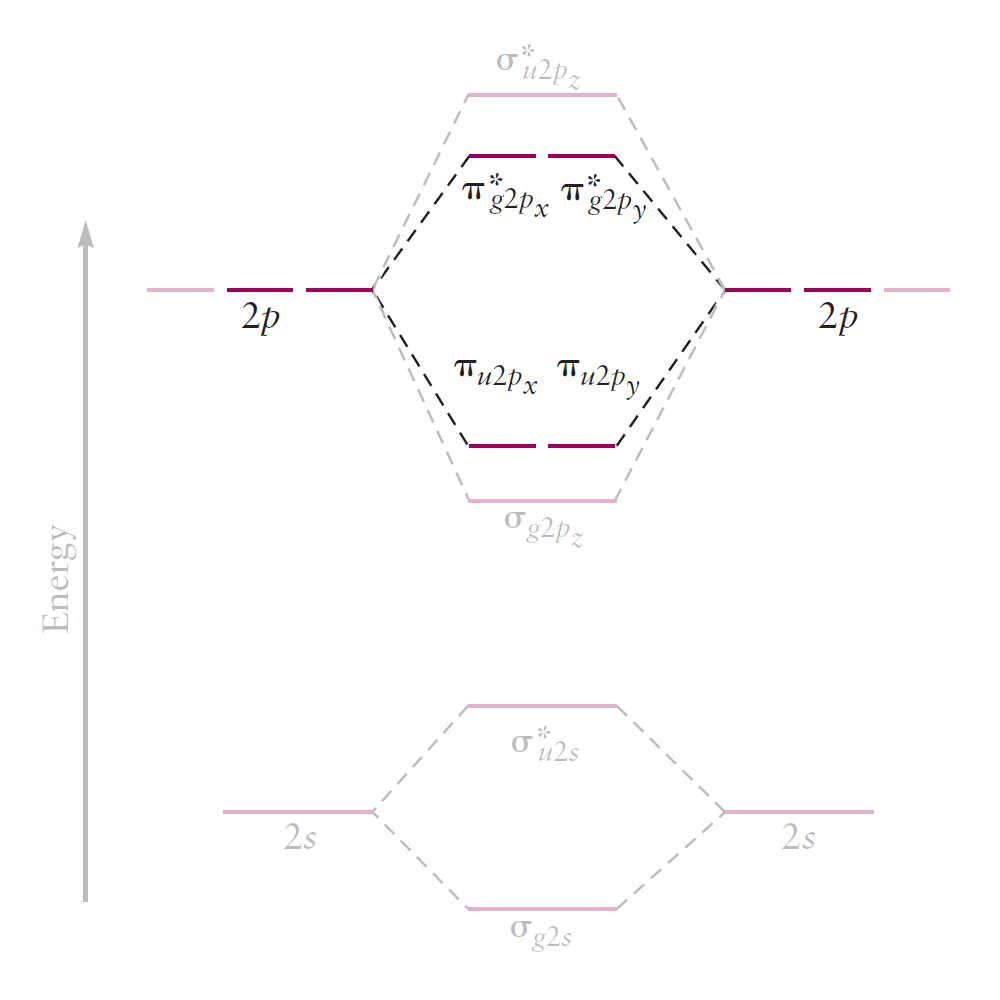

In plain terms, $\sigma_{g2s}$ decreases in energy, while $\sigma_{g2p_{z}}$ increases in energy. The updated correlation diagram below reflects these changes.

Due to the drastic increase in energy of $\sigma_{g2p_{z}}$, the order among $\sigma_{g2p_{z}}$ and $\pi_{u2p_x} / \pi_{u2p_y}$ is now reversed, as expected.

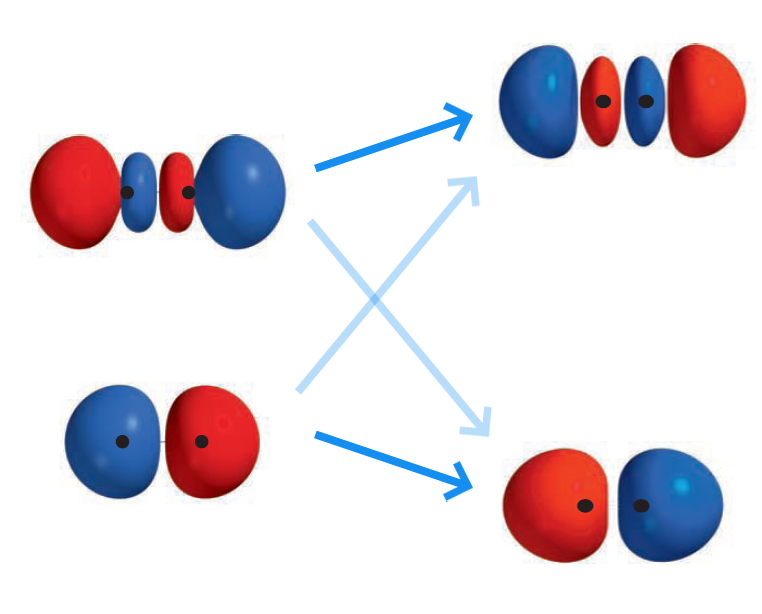

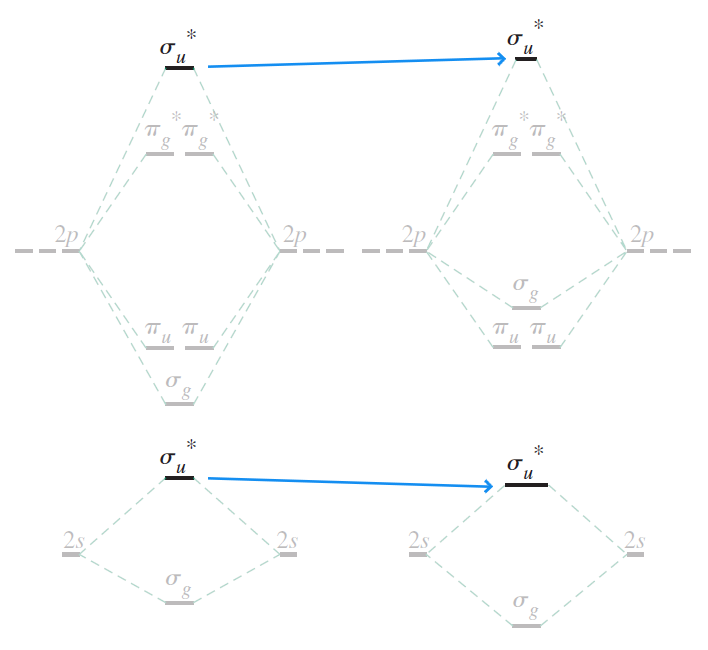

By mixing the two $\sigma_u$ MOs, we obtain two new $\sigma_{u \, \vert \, \text{improved}}$ MOs: $\sigma_{u2s \, \vert \, \text{improved}}^{\ast}$ and $\sigma_{u2p_{z} \vert \, \text{improved}}^{\ast}$

where $\tilde{c_3} = a_3 / c_3, \tilde{c_4} = a_4 / c_4$.

Like the $\sigma_g$ MOs, $\sigma_{u2s}^{\ast}$ decreases in energy as $\sigma_{u2p_{z}}^{\ast}$ increases in energy.

Unlike the $\sigma_g$ MOs, the changes in energy is barely noticable. This is because $\sigma_{u2s}^{\ast}$ and $\sigma_{u2p_{z}}^{\ast}$ overlap poorly - by inspection, roughly equal amounts of constructive and destructive interference is to be predicted. In hindsight, the mixing of the two was not necessary.

Summary

From $ \text{Li}_2 $ to $ \text{N}_2 $, the energy levels of $ 2s $ and $ 2p_z $ orbitals are close enough for mixing to occur. Instead of directly mixing the $ 2s $ and $ 2p_z $ orbitals, their $\sigma _{g}$ LCAO-MOs ($\sigma _{g2s}$ and $\sigma _{g2p_z}$) can be further mixed to produce more accurate MOs. As $\sigma _{g2s}$ and $\sigma _{g2p_z}$ are mixed, the energy levels of $\sigma _{g2p_z}$ and $\pi _{u2p_x}$ / $\pi _{u2p_y}$ become reversed.

Footnotes

-

For all LCAO below, we have sneakily ignored AOs of $n = 3$ and above (ex. $3s$, $3p$, $3d$, $4s$, etc.). This is because AOs of higher energy contribute very little to the MOs we are interested in; these AOs are also unnecessary for our explanation. ↩

-

The term “mix” is really a short-hand way of saying “interfere”. For example, “the AOs $2s^A$ and $2s^B$ mix to form bonding and antibonding MOs” really mean “the AOs $2s^A$ and $2s^B$ interfere constructively (to form a bonding MO) and destructively (to form an antibonding MO)” ↩

-

Nitrogen seems like a borderline case, but the fact that their AOs overlap very well (a point indirectly made later in the article) makes up for its large energy difference. ↩