Atomic Term Symbols: Part 1 - The Preliminaries

Introduction

This article is an in-depth explanation on atomic term symbols based on Quantum Chemistry by Levine to supplement chapter 8 of Physical Chemistry: A Molecular Approach by McQuarrie. A good understanding of preceding chapters, notably chapters 6 and 7, is required.

The notation used in this article is based on the latter textbook.

Part 1 deals with the quantum mechanics of multi-electron atoms, while Part 2 and Part 3 are devoted to atomic term symbols.

The Atomic Hamiltonian

We start with the Hamiltonian for multi-electron atoms. The Hamiltonian for an atom with $n$ electrons and a nuclear charge of $Z$, in atomic units, is as follows.

\[\hat{H} = \sum_{i\,=\,1}^{n}\left ( -\frac{1}{2}\nabla_i^2 \right ) + \sum_{i\,=\,1}^{n}\left ( -\frac{Z}{r_i} \right ) + \sum_{i}\sum_{j\,>\,i} \left ( \frac{1}{r_{ij}} \right )\]For now, the potential term of $\hat{H}$ only includes Coulombic interactions. We ignore terms arising from interactions such as spin-orbit interaction or spin-spin interaction, as their contributions are small.1

The eigenfunctions of $\hat{H}$, $\psi \left(r_1, \theta_1, \phi_1, \sigma_1;\,r_2, \theta_2, \phi_2, \sigma_2;\, \cdots ;\,r_n, \theta_n, \phi_n, \sigma_n \right)$,2 are the energy states of helium. This $\psi$ can be obtained numerically (with near-exact results) or with approximations such as the Hartree-Fock self-consistent-field (SCF) method with Slater-type orbitals (STOs), which retains the orbital concept.

However, for our discussion of multi-electron atoms, there is no need to obtain such $\psi$. The exact details of $\psi$ are not important; what is important is the fact that $\psi$ is an eigenfunction of the operator $\hat{H}$. This will prove to be very important, as we discover other properties of $\hat{H}$ and $\psi$.

Complete Set of Commuting Observables

Consider a hydrogen-like atom with one electron. The $\psi$ of this system are the atomic orbitals. As you may know, $\hat{H}$ commutes not with $\bold{\hat{l}}$, the orbital angular momentum operator, but with its square, $\hat{l}^2$.3 As a result, $\psi$ can be chosen to be an eigenfunction of both $\hat{H}$ and $\hat{l}^2$. Even if $\psi$, an eigenfunction of $\hat{H}$, happens to not be an eigenfunction of $\hat{l}^2$, a suitable linear combination involving $\psi$ must be an eigenfunction of $\hat{l}^2$.

Physically, this means that particular energy states have a definite value of the observable $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$ in addition to $E$, the energy.

The same can be said with $\hat{l}_z$,3 the z-component of $\bold{\hat{l}}$, which commutes with $\hat{H}$. Furthermore, $\hat{l}_z$ commutes with $\hat{l}^2$. In total, this means that a $\psi$ can be chosen to be an eigenfunction of $\hat{H}$, $\hat{l}^2$, and $\hat{l}_z$ simultaneously. Physically, this means that particular energy states have a definite value of $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, and $l_z$ at the same time.

The electronic spin operators are similar in this regard. $\hat{H}$ commutes with $\hat{s}^2$ and $\hat{s}_z$3 as $\hat{H}$ is not dependent on electronic spin. $\hat{s}^2$ and $\hat{s}_z$ commute with each other (more precisely, are defined in a way such that they commute with each other). Any orbital angular momentum operator ($\hat{l}^2$ or $\hat{l}_z$) commutes with any spin operator ($\hat{s}^2$ or $\hat{s}_z$) because the former is dependent on spatial variables only, while the latter is dependent on spin variables.

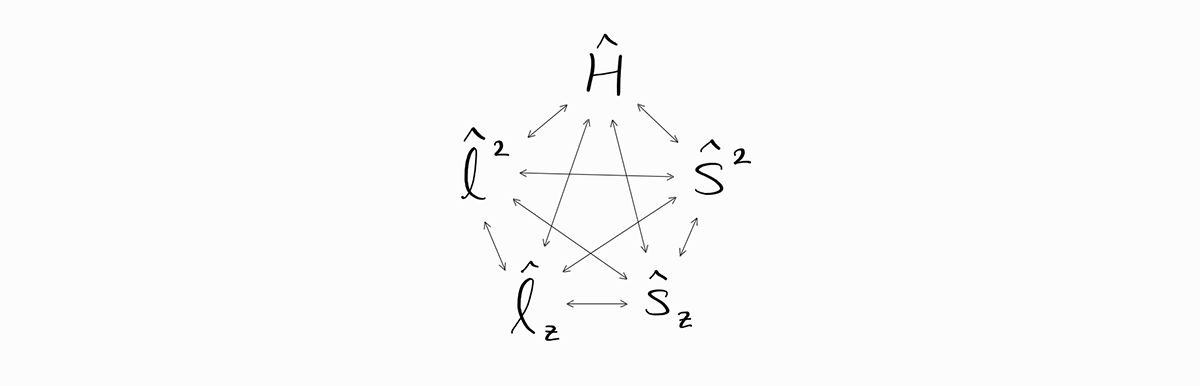

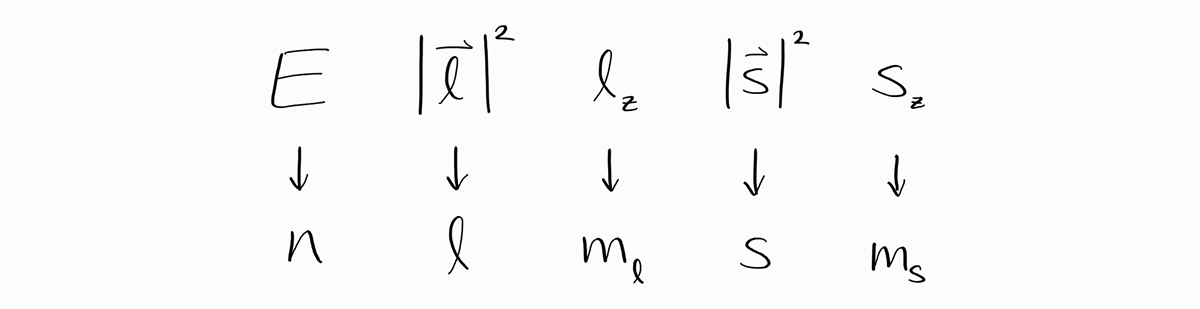

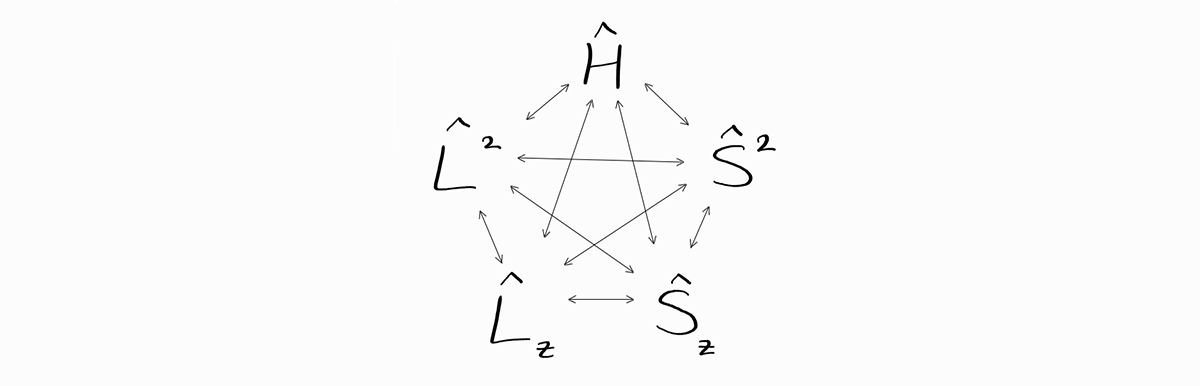

As a result, the operators $\hat{H}$, $\hat{l}^2$, $\hat{l}_z$, $\hat{s}^2$, and $\hat{s}_z$ all commute with each other as shown below.

Mathematically, this means that particular wave functions ($\psi$) are eigenfunctions of $\hat{H}$, $\hat{l}^2$, $\hat{l}_z$, $\hat{s}^2$, and $\hat{s}_z$; thus, they satisfy the following.

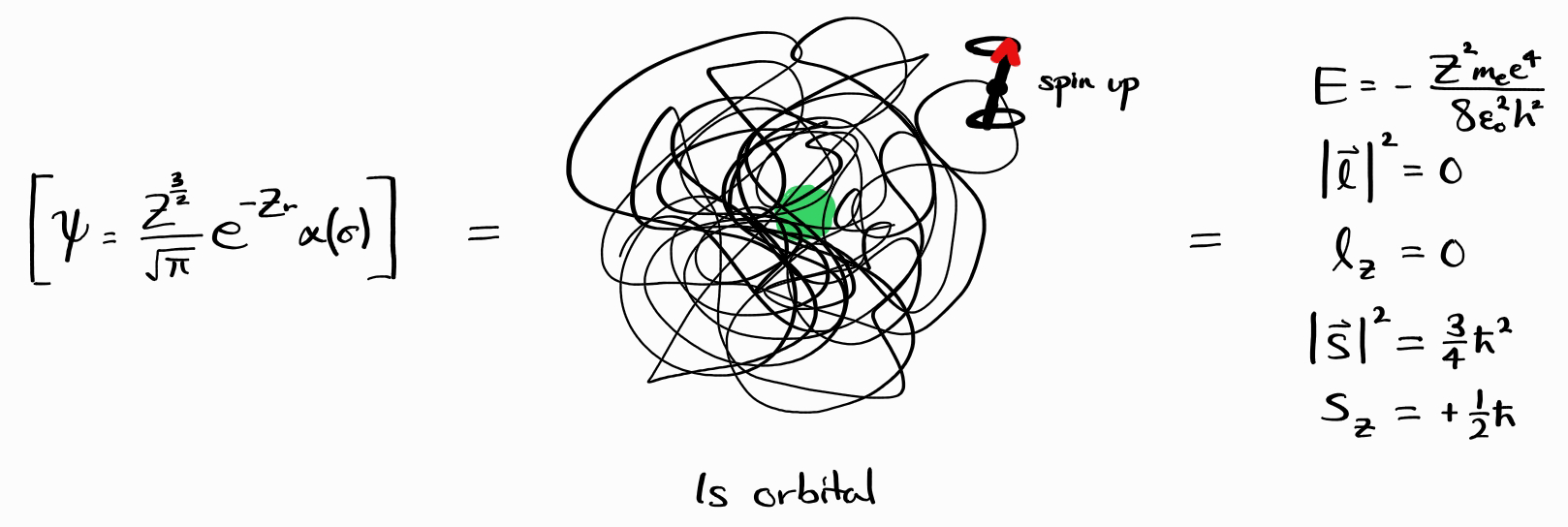

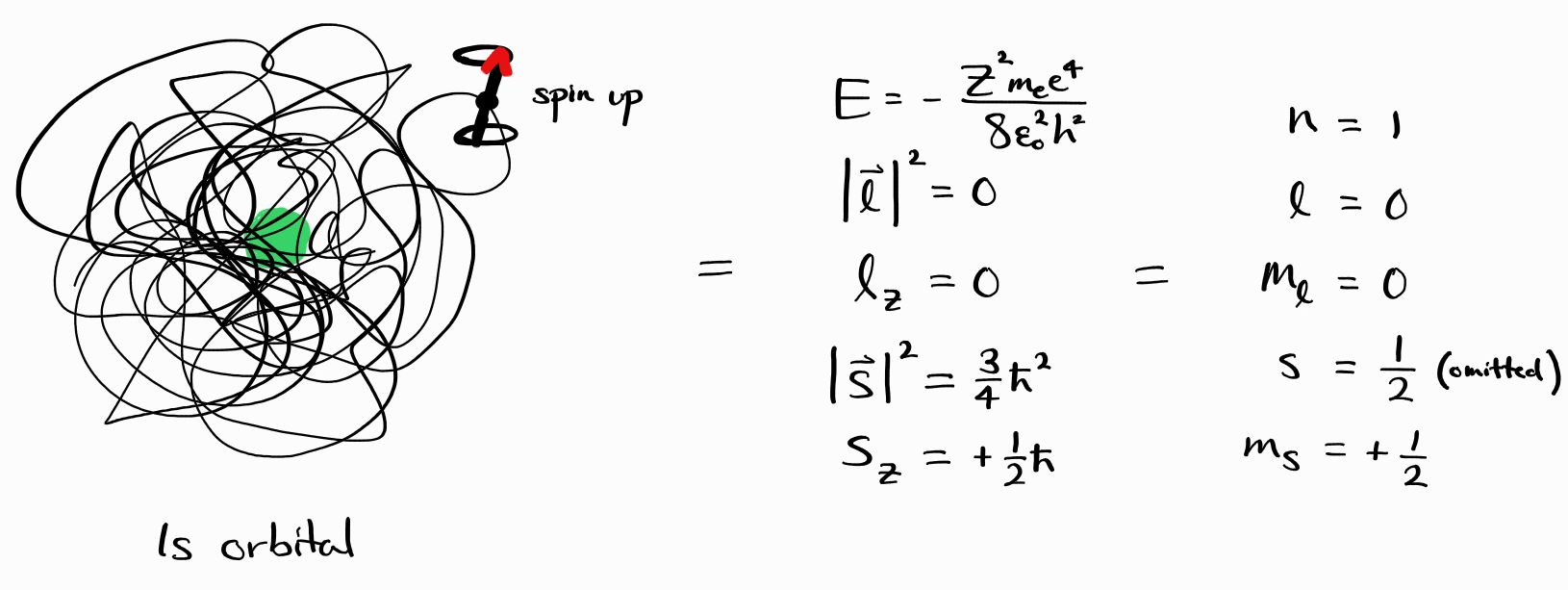

\[\hat{H} \psi = E \psi\] \[\hat{l}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{l} \right|^2 \psi\] \[\hat{l}_z \psi = l_z \psi\] \[\hat{s}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{s} \right|^2 \psi\] \[\hat{s}_z \psi = s_z \psi\]Physically, this means that such energy states have a definite value of observables $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$, and $s_z$. For example, the wave function $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \alpha(\sigma)$ (which translates to one electron in a $1s$ orbital, spin up) has a definite value of $E = -Z^2 m_e e^4/8\epsilon_0^2h^2$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2 = 0$, $l_z = 0$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2 = 3\hbar^2/4$, and $s_z = +\hbar/2$ (in SI units).

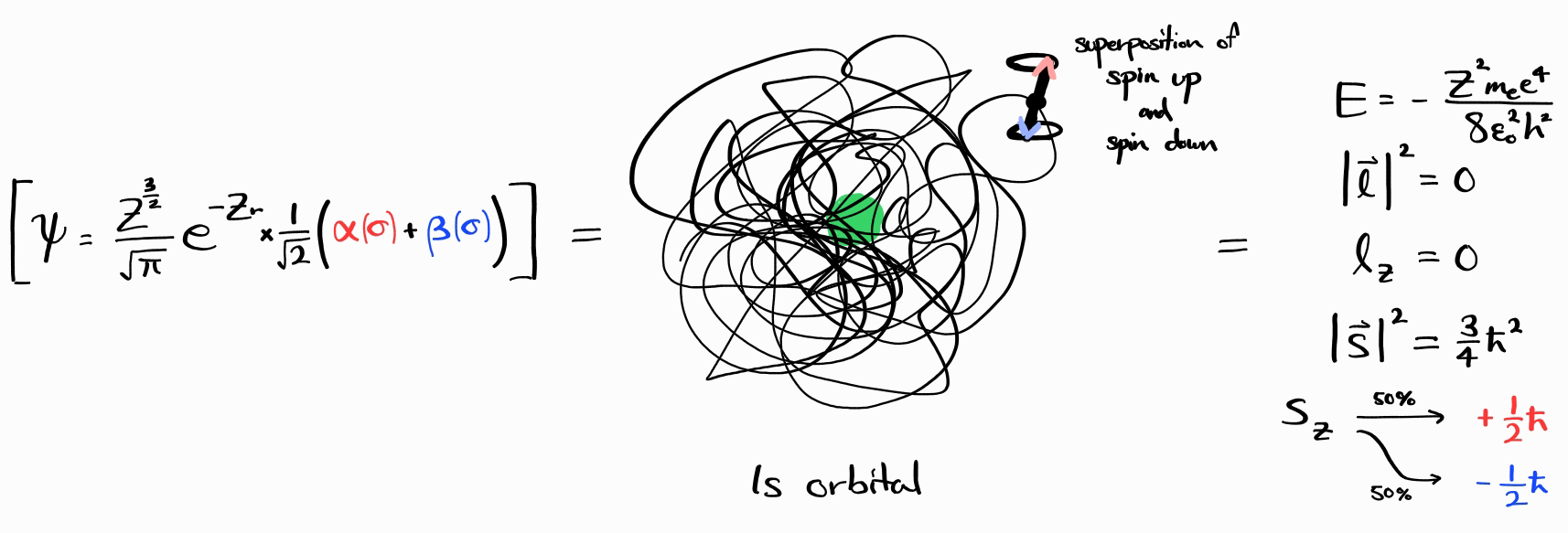

Any energy state can be expressed as a linear combination of degenerate energy states with a definite value of $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$, and $s_z$. For example, consider the wave function $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \times \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(\alpha(\sigma) + \beta(\sigma)\right)$.

This wave function is an energy state, as it has a definite value of $E$, which is the same as the previous example. In fact, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, and $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$ of this wave function is the same as the previous example.

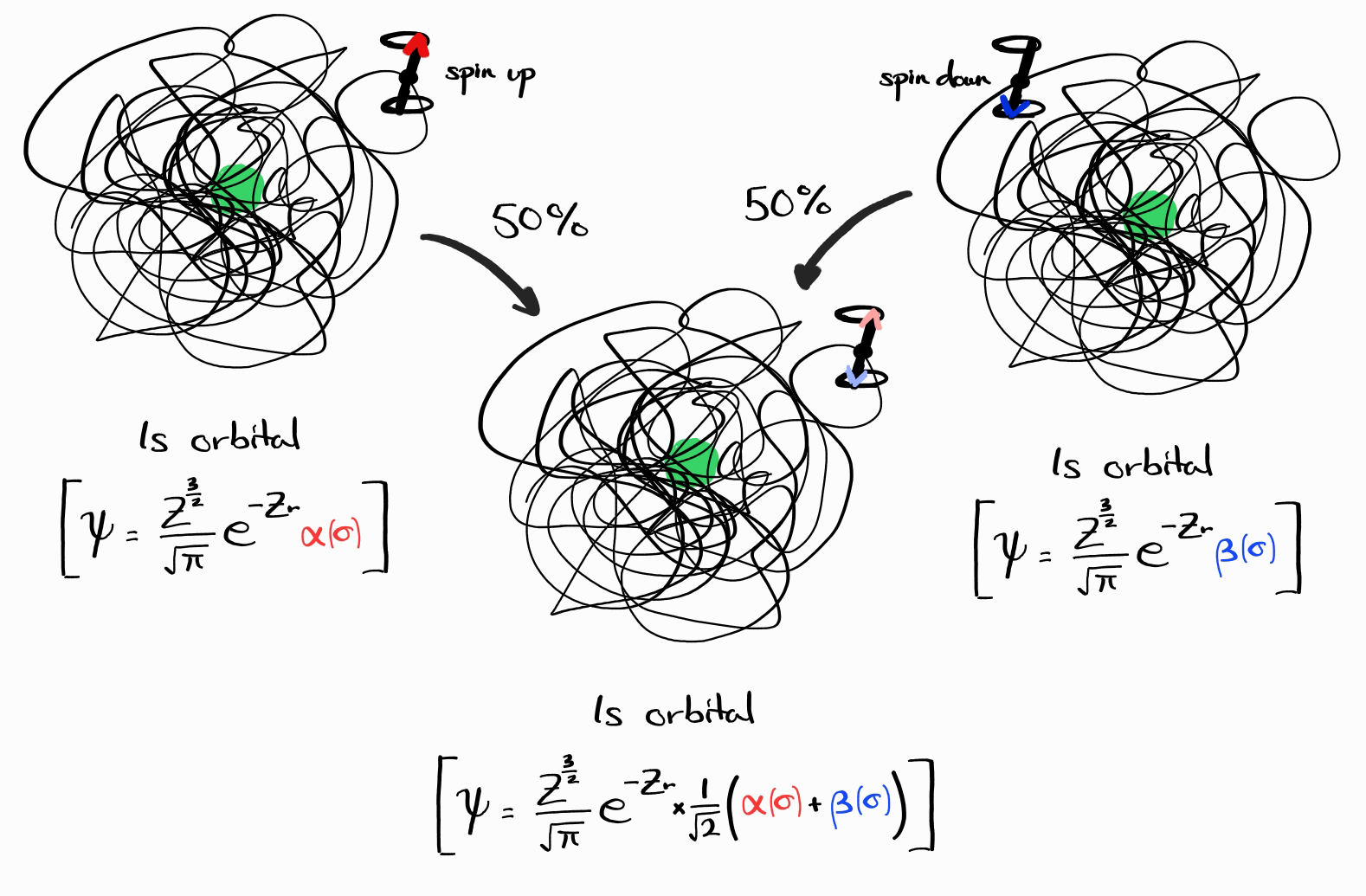

However, the spin of the electron ($s_z$) is not definite, as it is a superposition of spin up ($\alpha(\sigma)$, $s_z = +\frac{\hbar}{2}$) and spin down ($\beta(\sigma)$, $s_z = -\frac{\hbar}{2}$). Upon observation of $s_z$, 50% of the time it is spin up, and 50% of the time it is spin down.

Cases like this infinitely exist. However, all of these wave functions can be expressed as linear combinations of wave functions with definite $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$, and $s_z$. For $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \times \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(\alpha(\sigma) + \beta(\sigma)\right)$, this wave function is a linear combination of $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \alpha(\sigma)$ (always spin up) and $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \beta(\sigma)$ (always spin down). Mathematically, these two are part of the eigenbasis of $\hat{H}$.

When explaining the various facets of quantum mechanics, it is much easier to deal with wave functions that have a definite value of $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $\cdots$, etc. than wave functions that do not. As a simple example, let us ask a question like “what is the degeneracy of this energy level (number of energy states with the same energy)?” The technical answer would be:

Infinitely many energy states have the same energy, but those states can be decomposed into two (for example, $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \alpha(\sigma)$ and $\psi = \frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \beta(\sigma)$) independent energy states.

This is a bit cumbersome compared to:

The degeneracy of this energy level is 2.

Therefore, for the sake of convenience and readability, we will now limit our discussion of energy states to ONLY energy states with a definite value of $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$, and $s_z$. On that note,

An energy state of a hydrogen-like atom is completely characterized by

\[E,\: \left| \bold{l} \right|^2,\: l_z,\: \left| \bold{s} \right|^2,\: \text{and}\: s_z\]

This means that instead of describing $\psi$ by its functional form $(\frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \alpha(\sigma))$, we can describe it by specifying its $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$, and $s_z$. These observables are special in this regard, and thus they have a special name: a complete set of commuting observables(CSCO).

In practice, it is a bit awkward to list the exact value of the five observables everytime we want to refer to an energy state. Instead, we can call these values (and thus the energy state) with the associated quantum numbers: $n, l, m_l, s, m_s$.

These quantum numbers arise from the derivation of $\psi$, and as a consequence of the boundary conditions imposed on $\psi$, they are integers or half-integers.

Following are the relationship between observables and their quantum numbers for hydrogen-like atoms, in SI units.

\[\hat{H} \psi = E \psi = -\frac{Z^2m_ee^4}{8\epsilon_0^2h^2n^2} \psi\] \[\hat{l}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{l} \right|^2 \psi =l\left(l+1\right)\hbar^2 \psi\] \[\hat{l}_z \psi = l_z \psi = m_h \hbar \, \psi\] \[\hat{s}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{s} \right|^2 \psi =s\left(s+1\right)\hbar^2 \psi\] \[\hat{s}_z \psi = s_z \psi = m_s \hbar \, \psi\]When specifying a particular $\psi$, we can substitute $E$ with the principle quantum number $n = 1,\, 2,\, 3,\, \cdots$, as

\[E = -\frac{Z^2m_ee^4}{8\epsilon_0^2h^2n^2}\]We can substitute $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$ with the (orbital) angular momentum quantum number $l = 0, \,1, \,2, \,\cdots,\, n$, as

\[\left| \bold{l} \right|^2=l\left(l+1\right)\hbar^2\]We can substitute $l_z$ with the magnetic quantum number $m_l = -l,\, -l+1,\, \cdots, \,0, \,\cdots, \,+l-1, \,+l$, as

\[l_z = m_h \hbar\]We can substitute $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$ with $s$, as

\[\left| \bold{s} \right|^2 =s\left(s+1\right)\hbar^2\]As there is only a single electron for hydrogen-like atoms, $s=1/2$. Therefore, in general chemistry and elsewhere, $s$ is often omitted as it does not convey any additional information. The reason this is here is because we will deal with multi-electron atoms with more complicated electron spin, at a later date.

Lastly, we can substitute $s_z$ with the spin quantum number $m_s$, as

\[s_z = m_s \hbar\]Like $m_l$, $m_s = -s,\, -s+1,\, \cdots, \,+s-1, \,+s$. As $s = 1/2$, $m_s$ must be either $+1/2$ (spin up) or $-1/2$ (spin down).

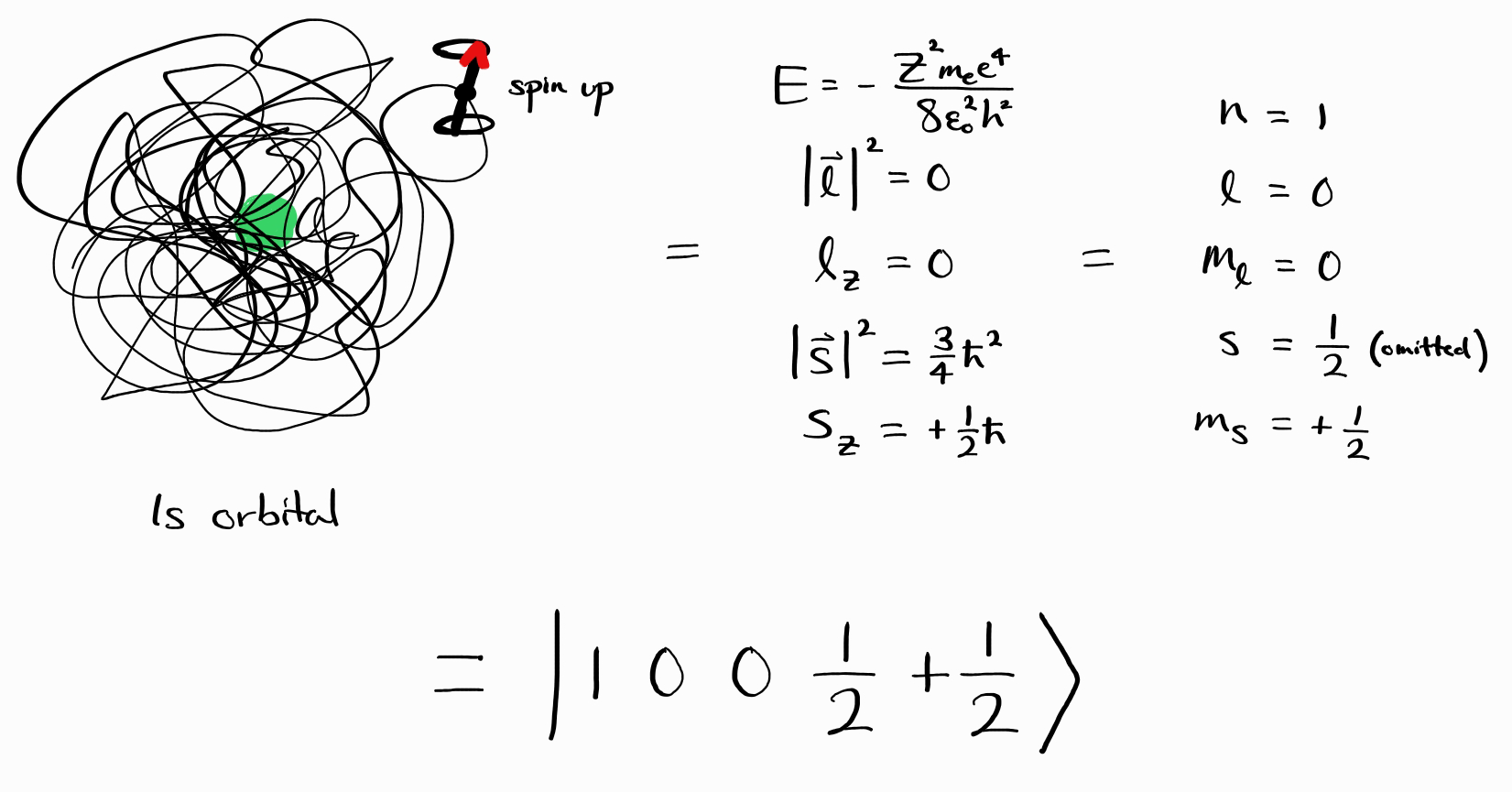

Our last example dealt with a $1s$ orbital, spin up energy state $\psi$. This energy state was described either with its functional form (of $(\frac{Z^\frac{3}{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-Zr} \alpha(\sigma))$), or by its complete set of commuting observables $E$, $\left| \bold{l} \right|^2$, $l_z$, $\left| \bold{s} \right|^2$, and $s_z$. Now, we can describe it very concisely with a set of quantum numbers: $\left(n, l, m_l, s, m_s\right) = (1, 0, 0, 1/2, +1/2)$.

We can adopt the bra-ket notation, where a vector (a wave function) is denoted by a bra($|$) and a ket($ \rangle $). A very apt name for an energy state would be a list of its quantum numbers ($n\,l\,m_l\,s\,m_s$). This name goes inbetween the bra and the ket to denote the energy state $\psi$.

\[\psi = \psi_{\left(n, \,l, \,m_l,\, s,\, m_s\right)} = \left |\, n\,l\,m_l\,s\,m_s\,\right \rangle\]Thus, the $1s$ orbital, spin up energy state $\psi$ is equivalent to $\left |\, 1\,0\,0\,\frac{1}{2}\,+\frac{1}{2}\,\right \rangle$.

To conclude, this section can be condensed into a single statement:

An energy state of a hydrogen-like atom is characterized by orbital and spin quantum quantum numbers. With the bra-ket notation:

\[\psi = \left |\, n\,l\,m_l\,s\,m_s\,\right \rangle\]

Multi-electron Atom

It would be nice if the energy states of multi-electron atoms are described completely by quantum numbers similar to those of hydrogen-like atoms.

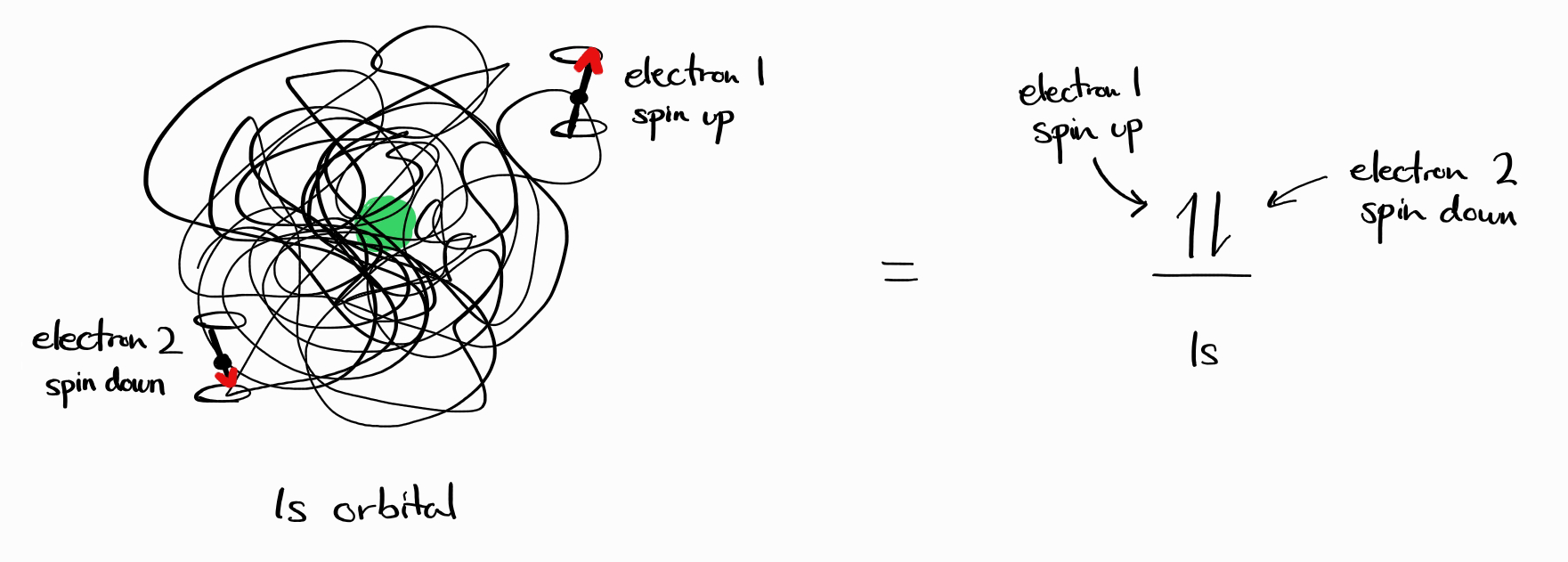

One speculation one might have is that such energy states are described by quantum numbers for each electron. For example, an energy state of a neutral helium atom might be described as $ \left |\, n_1\,l_1\,m_{l1}\,s_1\,m_{s1};\,n_2\,l_2\,m_{l2}\,s_2\,m_{s2}\,\right \rangle$, as there are two electrons. For the ground state helium atom, perhaps $ \left |\, 1\,0\,0\,\frac{1}{2}\,+\frac{1}{2};\,1\,0\,0\,\frac{1}{2}\,-\frac{1}{2}\,\right \rangle$ is appropriate?

If this seems too convenient, this is because it is incorrect. There are two complementary reasons why energy states cannot be described by quantum numbers of each electron.

First, we go back to our discussion of hydrogen-like atoms. For an energy state to be described by quantum numbers, the operator associated with the observable/quantum number (i.e. $\hat{s}_z$ for $m_s$) must commute with the Hamiltonian, $\hat{H}$.

For a helium atom to be denoted $ \left |\, n_1\,l_1\,m_{l1}\,s_1\,m_{s1};\,n_2\,l_2\,m_{l2}\,s_2\,m_{s2}\,\right \rangle$, operators $ \hat{H} _{1} $, $ \hat{l} _{1} ^{2} $, $ \hat{l} _{1z} $, $ \hat{s} _{1} ^{2} $, $ \hat{s} _{1z} $, $ \hat{H} _{2} $, $\hat{l} _2 ^2$, $\hat{l} _{2z}$, $\hat{s} _2 ^2$, and $\hat{s} _{2z}$ must commute with $\hat{H}$. Even ignoring $\hat{H} _1$ and $\hat{H} _2$,4 operators $\hat{l} _1^2$, $\hat{l} _{1z}$, $\hat{s} _1^2$, $\hat{s} _{1z}$, $\hat{l}_2^2$, $\hat{l} _{2z}$, $\hat{s} _2^2$, and $\hat{s} _{2z}$ do not commute with $\hat{H}$.

This means that such helium energy state does not have definite values of observables $E$, $\left| \bold{l} _1 \right| ^2$, $l _{1z}$, $\left| \bold{s} _1 \right| ^2$, $s _{1z}$, $\left| \bold{l} _2 \right| ^2$, $l _{2z}$, $\left| \bold{s} _2 \right| ^2$ and $s _{2z}$, as such energy state is not an eigenfunction of all of the operators listed above. Consequently, it is not possible to assign the quantum numbers $l _1\,m _{l1}\,s _1\,m _{s1};\,l _2\,m _{l2}\,s _2\,m _{s2}$, and the notation $ \left |\, n _1\,l _1\,m _{l1}\,s _1\,m _{s1};\,n _2\,l _2\,m _{l2}\,s _2\,m _{s2}\,\right \rangle$ is wrong.

Second, the scheme $ \left |\, n_1\,l_1\,m_{l1}\,s_1\,m_{s1};\,n_2\,l_2\,m_{l2}\,s_2\,m_{s2}\,\right \rangle$ implies that we can distinguish the two electrons: one is spin up and one is spin down. However, all electrons are identical and it is impossible to distinguish between any electrons in an atom. For the ground state helium, (1) there is no “electron 1” and “electron 2” and (2) no electron is simply spin up or down, but any electron can be spin up or spin down upon measurement.

If so, what are the quantum numbers that completely describe an energy state of a multi-electron atom? Another way of saying this would be “which operators commute with the Hamiltonian and with each other to form a complete set of commuting observables?”

In classical mechanics, angular momentum is a vector and therefore adds vectorally. In equation form, it would look something like this.

\[\bold{L} = \sum_i \bold{l}_i\]Quantum mechanics has angular momentum operators, which also adds vectorally. For starters, the total[^7] orbital angular momentum operator $\hat{L}$ is defined as the sum of all orbital angular momentum operator $\hat{l}_i$ for all electrons.

\[\hat{L} = \sum_i \hat{l}_i\]This is the orbital angular momentum operator of the entire atom. The operators derived from $\hat{L}$, $\hat{L}^2$ and $\hat{L} _z$, commute with each other, as well as with $\hat{H}$. Note that as $\hat{L} _z$ is the z-component of $\hat{L}$ and $\hat{l} _{iz}$ is the z-component of $\hat{l} _{i}$

\[\hat{L}_z = \sum_i \hat{l}_{iz}\]The total[^7] spin operator $\hat{S}$ is defined as the sum of all spin operators $\hat{s}_i$ for all electrons.

\[\hat{S} = \sum_i \hat{s}_i\]This is the spin operator of the entire atom. The operator $\hat{S}^2$ and $\hat{S}_z$ commute with each other, as well as with $\hat{H}$. Also note that

\[\hat{S}_z = \sum_i \hat{s}_{iz}\]As expected, any orbital angular momentum operator ($\hat{L}^2$ or $\hat{L}_z$) commutes with any spin operator ($\hat{S}^2$ or $\hat{S}_z$). Similar to hydrogen-like atoms, the operators $\hat{H}$, $\hat{L}^2$, $\hat{L}_z$, $\hat{S}^2$, and $\hat{S}_z$ all commute with each other as shown below.

This means that energy state $\psi \left(r_1, \theta_1, \phi_1, \sigma_1;\,r_2, \theta_2, \phi_2, \sigma_2;\, \cdots ;\,r_n, \theta_n, \phi_n, \sigma_n \right)$ can be described completely by the observables of $\hat{H}$, $\hat{L}^2$, $\hat{L}_z$, $\hat{S}^2$, and $\hat{S}_z$, as $\psi$ is an eigenfunction of all of the operators above.

\[\hat{H} \psi = E \psi\] \[\hat{L}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{L} \right|^2 \psi\] \[\hat{L}_z \psi = L_z \psi\] \[\hat{S}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{S} \right|^2 \psi\] \[\hat{S}_z \psi = S_z \psi\]Among the quantum numbers associated to these operators and observables, the multi-electron atom equivalent of the principle quantum number $n$ requires special treatment and will be discussed at the very end. For all other quantum numbers, in SI units,

\[\hat{L}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{L} \right|^2 \psi =L\left(L+1\right)\hbar^2 \psi\] \[\hat{L}_z \psi = L_z \psi = M_L \hbar \, \psi\] \[\hat{S}^2 \psi = \left| \bold{S} \right|^2 \psi =S\left(S+1\right)\hbar^2 \psi\] \[\hat{S}_z \psi = S_z \psi = M_S \hbar \, \psi\]We substitute the observable $\left| \bold{L} \right|^2$ with the total orbital angular momentum quantum number $L = 0, \,1, \,2,\, \cdots$ as

\[\left| \bold{L} \right|^2 =L\left(L+1\right)\hbar^2\]We substitute the observable $L_z$ with $M_L = -L,\, -L+1,\, \cdots, \,+L-1, \,+L$5 as

\[L_z = M_L \hbar\]We substitute the observable $\left| \bold{S} \right|^2$ with the total orbital angular momentum quantum number $S = 0, \,1/2,\, 1,\, 3/2,\, \cdots$ as

\[\left| \bold{S} \right|^2 =S\left(S+1\right)\hbar^2\]Unlike $L$, $S$ can take on half-integer values, and unlike hydrogen-like atoms, $S$ can take on a variety of values as there are many electrons.

We substitute the observable $S_z$ with $M_S = -S, \,-S+1, \,\cdots, \,+S-1, \,+S$5 as

\[S_z = M_S \hbar\]Depending on the value of $S$, $M_S$ can take integer values (e.g. $M_S = -1,\, 0,\, +1$ for $S = 1$) or half-integer values (e.g. $M_S = -1/2, \,+1/2$ for $S = 1/2$).

The observable $E$, energy, is problematic as although it is discrete, there is no formula to relate a quantum number to its corresponding observable. In fact, there is not much pattern at all! Instead of using quantum numbers like hydrogen-like atoms, we need a different scheme to describe energy in an easy way.

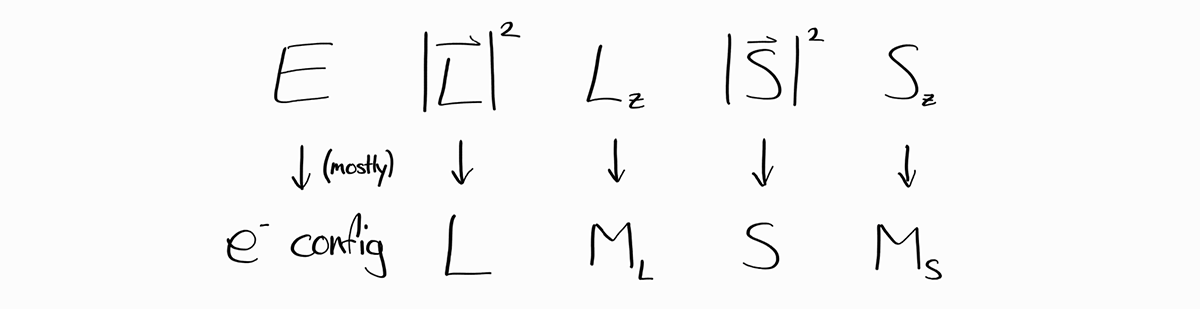

Luckily, for many electron configurations (ex. $1s^22s^22p^3$), no two energy states has the same $L$, $M_L$, $S$, and $M_S$. Therefore, in many cases, we can substitute $E$ with the electron configuration.

To sum up, for all cases, $E$, $L$, $M_L$, $S$, and $M_S$ can be used to specify an energy state. For many frequently encountered cases:

An energy state of a multi-electron atom is characterized by its electron configuration and orbital and spin quantum quantum numbers. With the bra-ket notation:

\[\psi = \left |\, (e^- \text{ config)}\,L\,M_L\,S\,M_S\,\right \rangle\]

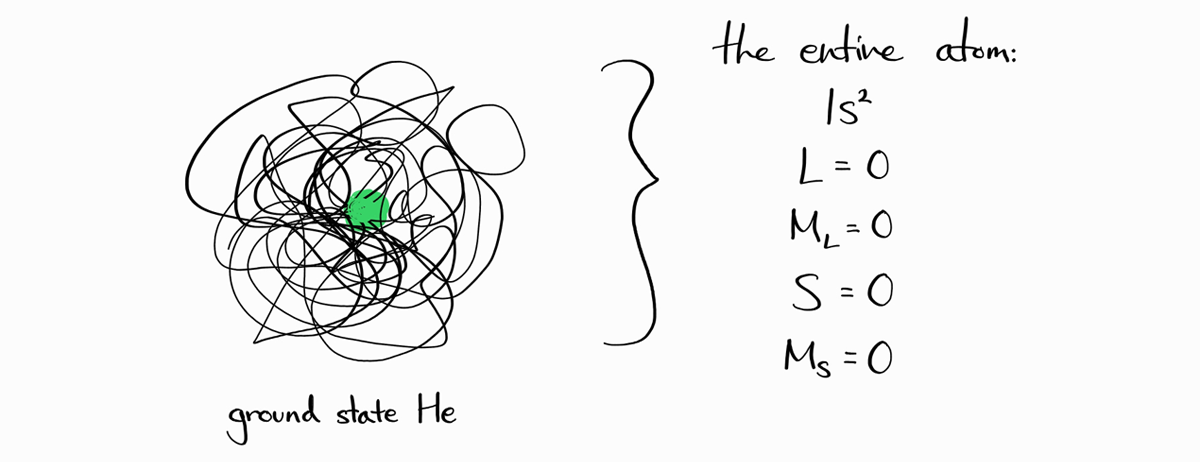

As an example, the ground state helium atom can be expressed as $\left |\, 1s^2\,0\,0\,0\,0\,\right \rangle$ with an electron configuration of $1s^2$, $L=0$, $M_L=0$, $S=0$, and $M_S=0$ (we haven’t explained how these values were calculated for now).

Footnotes

-

We are also ignoring nuclear mass and motion (rather considering them to be fixed in space) and nuclear spin. The wavefunction is technically an electronic wavefunction. ↩

-

The variable $\sigma_i$ is the spin variable of the $i^{\text{th}}$ electron. ↩

-

$\bold{\hat{L}}$, $\hat{L}^2$, $\hat{L}_z$, $\bold{\hat{S}}$, $\hat{S}^2$, $\hat{S}_z$ in the textbook for both hydrogen-like atoms and multi-electron atoms. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Defining these two operators is also problematic. ↩

-

For some reason, $M_L$ and $M_S$ do not have proper names and are just called $M_L$ and $M_S$. ↩ ↩2