More about my research

It all began with a challenge posed by Professor Insung S. Choi during a Physical Organic Chemistry lecture. While discussing the bent bond model of double bonds, he offered an A+ to the first student who could find the earliest mention of the σ-π description of double bonds, where σ bonds are described by valence bond theory and π bonds are described by molecular orbital theory. To my dismay, someone else had already found a review article that credits a 1934 paper by W. G. Penney1 before the end of the lecture.

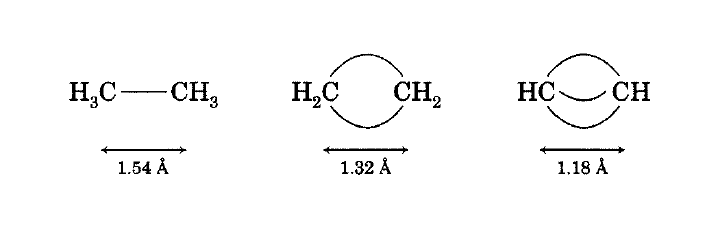

Bent bond description of ethane, ethylene, and acetylene.

Later that day, curious whether Penney’s work was truly the first, I carefully read through the paper and, to my surprise, found that it did not actually contain the σ-π description as we know it today. Eager to have another shot at the A+, I stayed up late digging through literature from that era. By morning, after an extensive search, I concluded that early discussions on the aromaticity of benzene, such as Hückel’s landmark paper in 19312 or Pauling’s 1933 paper3, were more appropriate. I presented my findings to the class and finally earned the A+.

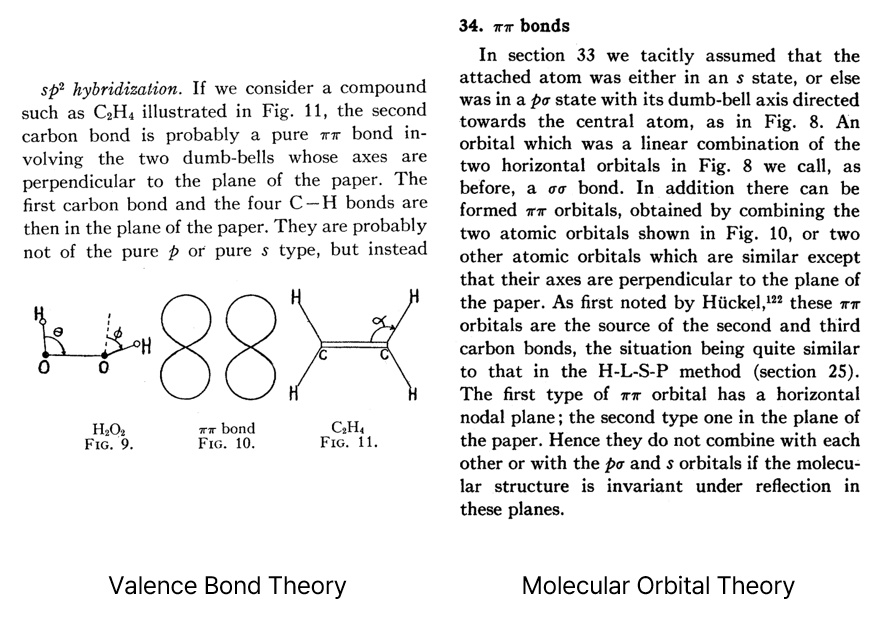

Snippets from Van Vleck’s review paper4 on the σ-π description of double bonds.

π bonds (then called ‘ππ bonds’) are explained with either

valence bond theory (left) or molecular orbital theory (right).

While exploring 1930s quantum theories, I came to see that much of chemistry is about distilling complex problems down to their essence, resulting in simple yet useful models. With this newfound appreciation for chemistry, I delved deeper, taking graduate-level courses such as Quantum Chemistry I, Statistical Mechanics I, Organic Synthesis I, and Organometallic Chemistry.

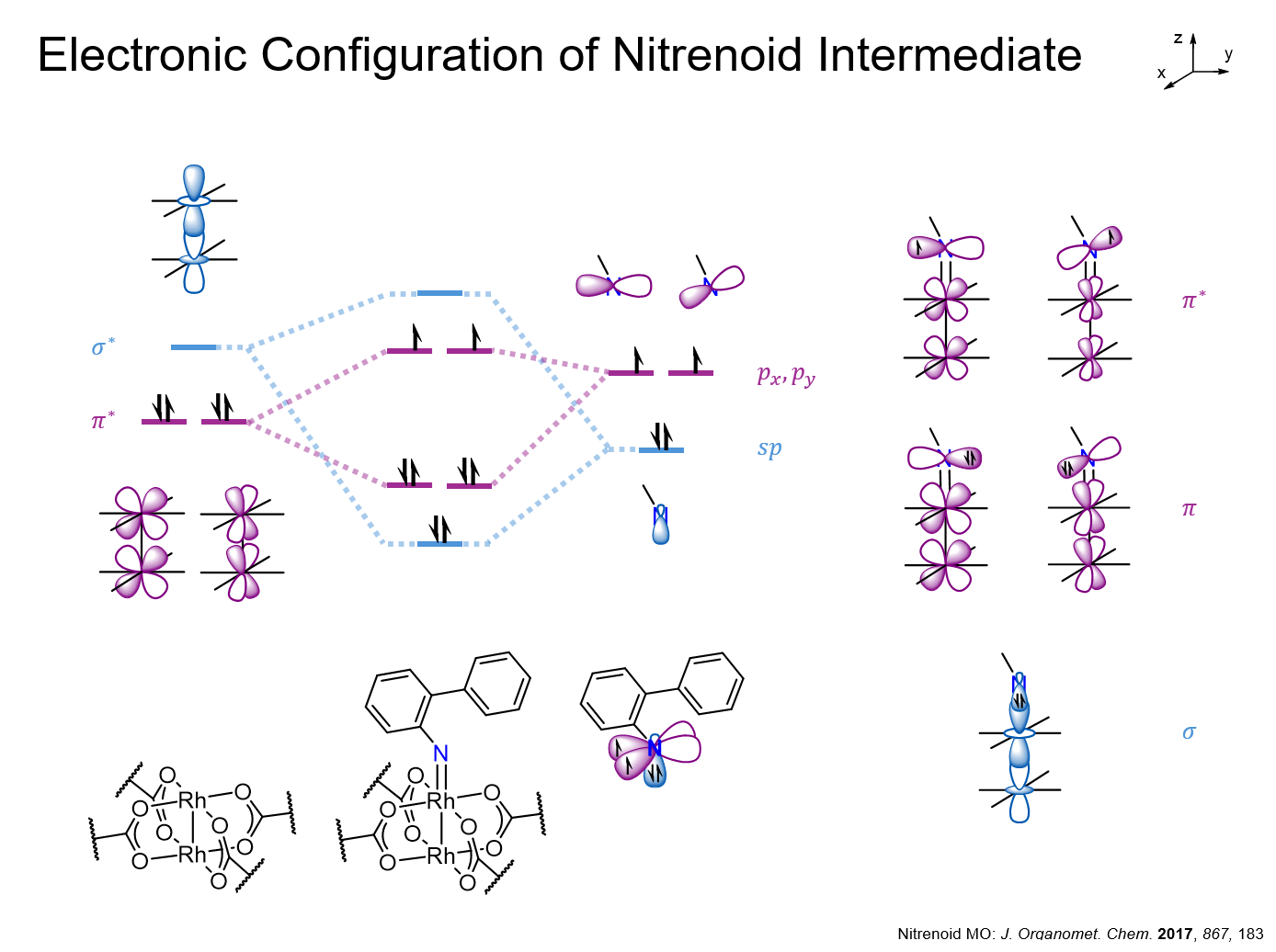

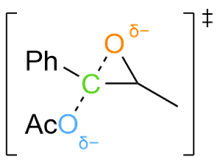

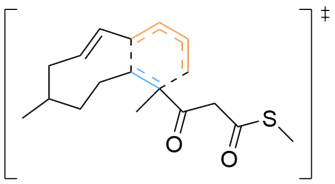

A slide I presented for my Organometallic Chemistry class.

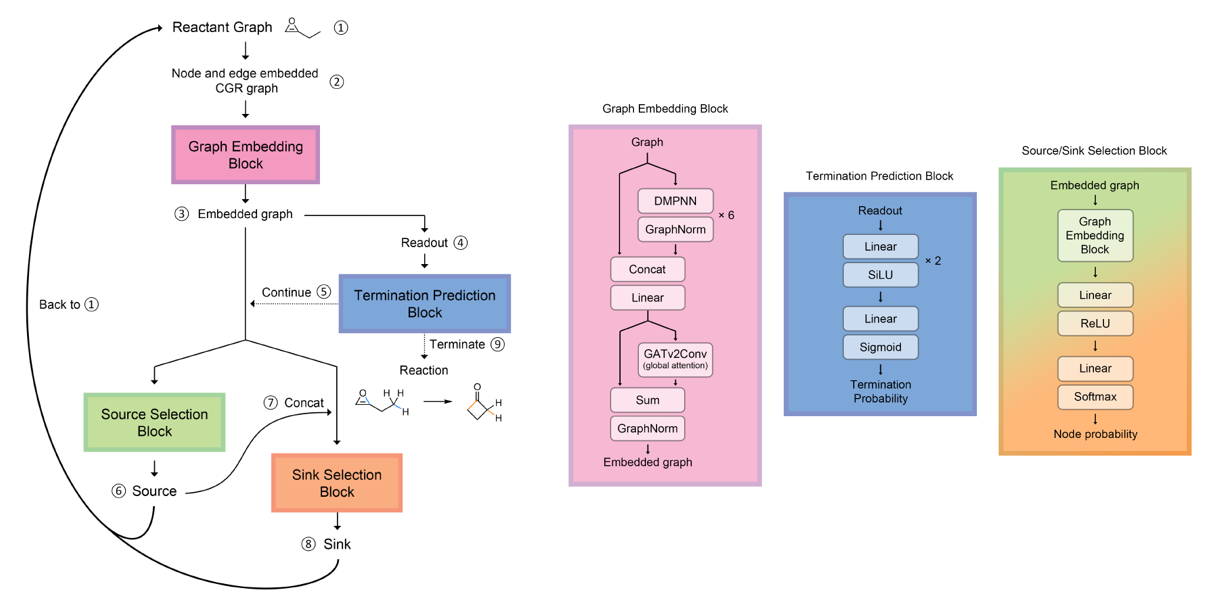

During this time, I was working in Professor Woo Youn Kim’s lab5, extending the capabilities of ACE-Reaction, a graph-theoretic method for predicting reaction mechanisms.6 I designed an autoregressive message passing neural network to suggest plausible reaction steps. I also adapted a mathematical formulation of an existing metric that originally applied only to balanced reactions to also handle unbalanced reactions. In addition, I integrated automatic transition state (TS) search routines into ACE-Reaction using both semi-empirical and density functional theory methods.

An autoregressive message passing neural network that I developed to suggest reaction mechanisms.

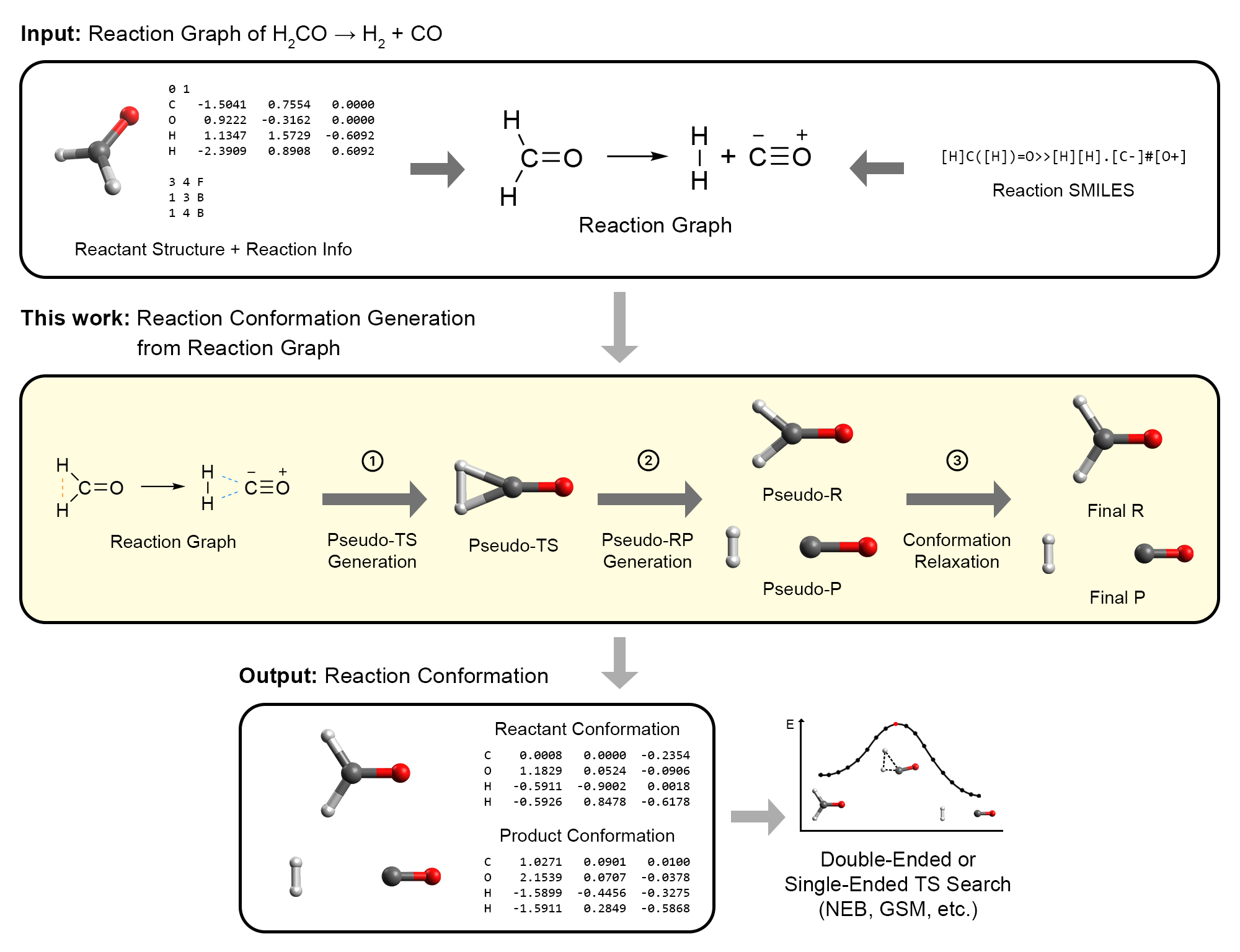

As part of this ongoing effort to expand ACE-Reaction, I also worked on AutoCG, which would completely transform my understanding of chemistry. AutoCG is an algorithm for generating reactant and product conformations for use in interpolation TS search methods.7 Its innovation lies in constructing a pseudo-TS structure that qualitatively resembles the true TS. The pseudo-TS is then gradually modified to produce reactant and product structures that are naturally well-aligned, in a manner similar to intrinsic reaction coordinate calculations.

Overview of our AutoCG algorithm.

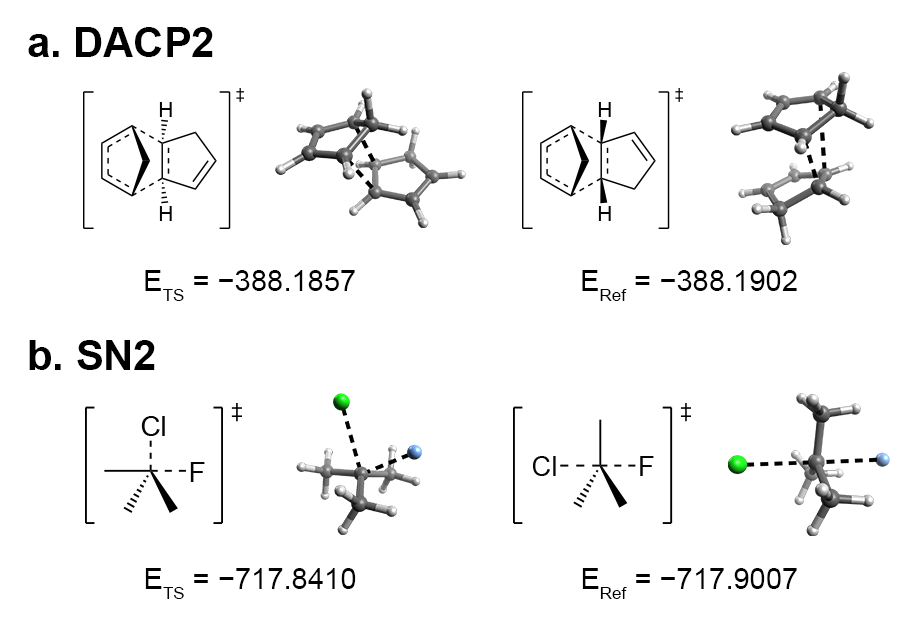

However, early iterations failed to yield the desired reactants or products in certain cases, such as the exo product in a Diels-Alder reaction. By analyzing common features among these failures, I concluded that controlling the R/S configuration at the reaction centers of the pseudo-TS structures would lead to the desired stereochemical configurations in the reactants and products.

(a) Exo (left) and endo (right) TS of a Diels-Alder reaction between two cyclopentadiene molecules.

(b) Frontside (left) and backside (right) TS of an SN2 reaction.

Implementing this solution was challenging because RDKit struggled to generate pseudo-TS structures with the correct stereochemistry. Drawing on my experience with molecular modeling kits and force field optimizations in Avogadro, I proposed a workaround: physically twisting two substituents of a stereogenic center to invert its R/S configuration, while continuously optimizing the overall structure using a force field. By combining RDKit’s force field gradients with SciPy’s optimizers, I was able to generate all relevant stereoisomers of a pseudo-TS from a single conformer. I also built an interface between AutoCG and CREST to sample pseudo-TS conformers, allowing us to capture variations in TS geometries, such as boat and chair forms.

R/S configuration inversion of a pseudo-TS of a Diels-Alder reaction and an SN2 reaction.

Reaction centers being inverted are highlighted in purple.

Our updated algorithm not only yielded reactant and product conformations that led to the desired TS structures but also, unexpectedly, produced TSs that were more stable than those of the original references. As a result, this work was published as a co-first-author article in the Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation.7 Follow-up research is currently underway, in collaboration with a total synthesis group, to enable rapid prediction of activation barriers and selectivity by integrating machine-learned interatomic potentials into AutoCG. Through this project, I realized how computational tools can reveal possibilities and insights even expert intuition might miss.

Various organic reactions obtained with AutoCG.

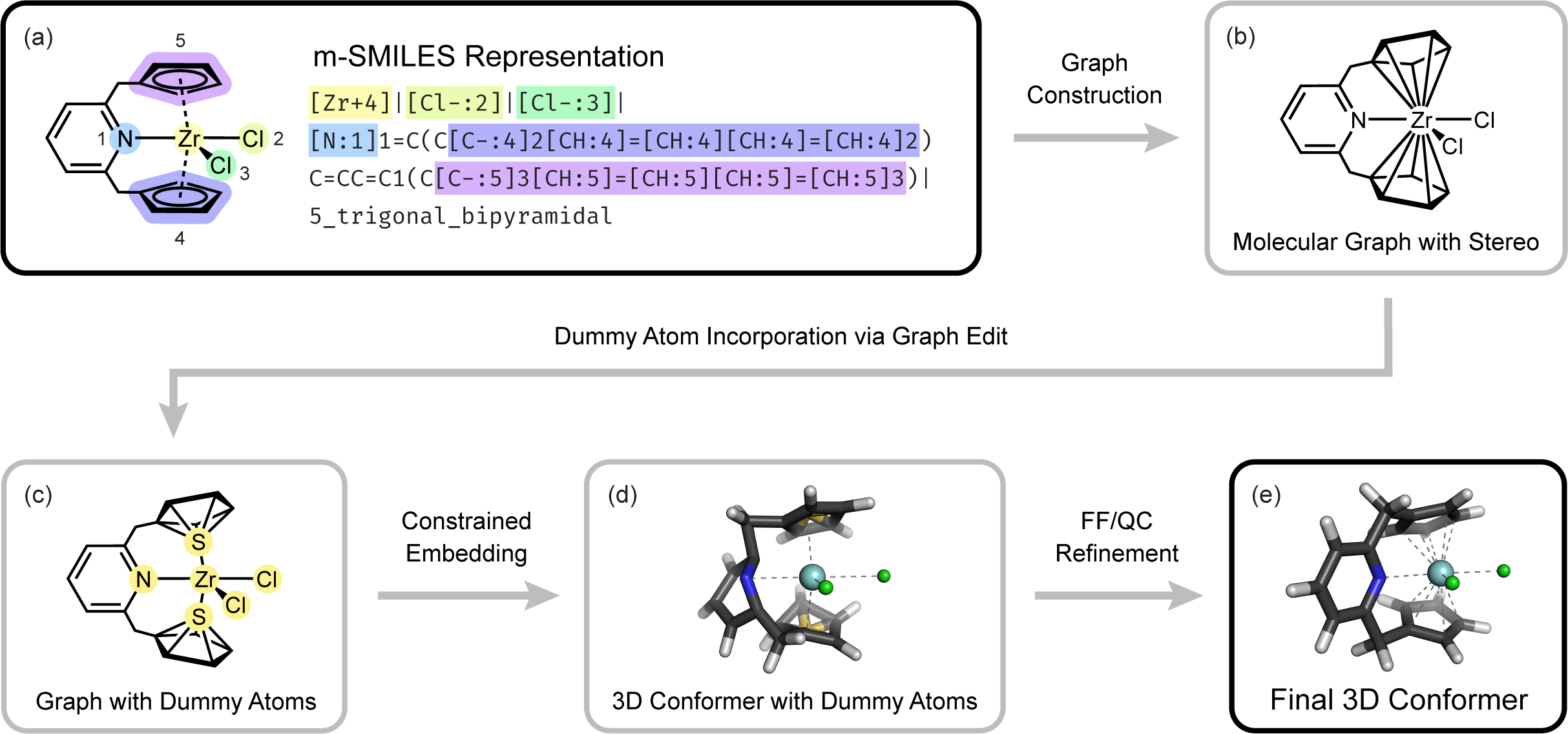

With my subsequent project, MetalloGen, I set out to push the boundaries of automated 3D conformer generation for organometallic compounds. Compared to its predecessors, MetalloGen supports a wider range of polydentate and polyhapto ligands, as well as more diverse geometry types. Drawing on my experience developing AutoCG and knowledge from Organometallic Chemistry, I proposed key ideas behind several core features of MetalloGen. These included introducing dummy atoms between polyhapto ligands and the metal center to enable 3D conformer embedding with RDKit, and refining embedded structures using both force field and quantum chemical methods.

Overview of our MetalloGen algorithm.

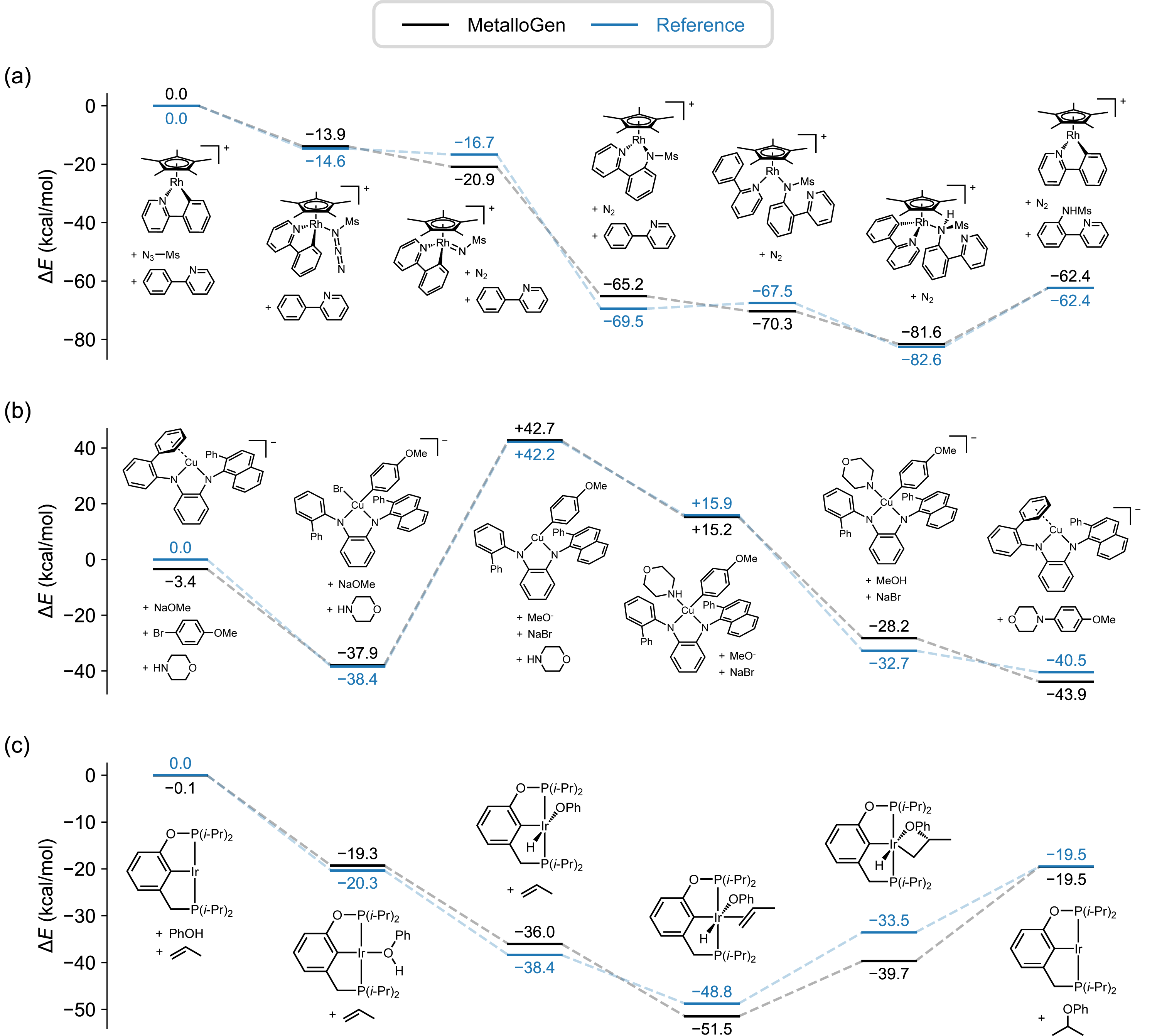

To set MetalloGen apart from earlier works, I proposed evaluating it on catalytic cycles involving unstable and transient intermediates, whereas prior methods were tested on stable, experimentally characterized complexes. We demonstrated that MetalloGen could generate a wide spectrum of catalytically relevant organometallic structures—from half-sandwich structures to σ- and π-complexes—resulting in positive and encouraging responses from reviewers. This work, published in the Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling,8 supports my broader goal: to develop computational tools that not only reproduce known chemistry but also guide the discovery and optimization of new functional systems.

(Left) Energy profiles of organometallic reactions generated with MetalloGen.

(Right) Intermediate structures generated with MetalloGen.

My journey so far has taught me how to transform curiosity into tools and methods that open new directions in molecular and materials science. From building algorithms like AutoCG and MetalloGen to designing machine learning components for ACE-Reaction, I have prepared myself to pursue research that connects physical principles with data-driven approaches. I am especially eager to develop interpretable AI models grounded in chemical theory, generate synthetic datasets through computational chemistry, and create generative models for materials discovery.

Looking ahead, my long-term goal is to lead a research group in academia or industry that advances chemistry and materials science through both computational and machine learning methods. I look forward to the day when my work can spark in others the same sense of curiosity I felt while poring over those early quantum chemistry papers, opening the way to discoveries we cannot yet imagine.

Footnotes

-

Penney, W. G. The theory of the structure of ethylene and a note on the structure of ethane. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A 1934, 144, 166–187. DOI: 10.1098/rspa.1934.0041 ↩

-

Hückel, E. Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem. I. Die Elektronenkonfiguration des Benzols und verwandter Verbindungen. Zeitschrift für Physik 1931, 70, 204–286. DOI: 10.1007/BF01339530 ↩

-

Pauling, L.; Wheland, G. W. The nature of the chemical bond. V. The quantum-mechanical calculation of the resonance energy of benzene and naphthalene and the hydrocarbon free radicals. Journal of Chemical Physics 1933, 1, 362–374. DOI: 10.1063/1.1749304 ↩

-

Van Vleck, J. H.; Sherman, A. The quantum theory of valence. Reviews of Modern Physics 1935, 7, 167–228. DOI: 10.1103/RevModPhys.7.167 ↩

-

Kim, Y.; Kim, J. W.; Kim, Z.; Kim, W. Y. Efficient prediction of reaction paths through molecular graph and reaction network analysis. Chemical Science 2018, 9, 825–835. DOI: 10.1039/C7SC03628K ↩

-

Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Kim, W. Y. Facilitating transition state search with minimal conformational sampling using reaction graph. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2025, 21, 2487–2500. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.4c01692 [PDF Article] [GitHub] ↩ ↩2

-

Lee, K.; Park, S.; Park, M.; Kim, W. Y. MetalloGen: Automated 3D conformer generation for diverse coordination complexes. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2025, 65, 11878−11891. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5c02074 [PDF Article] [GitHub] ↩